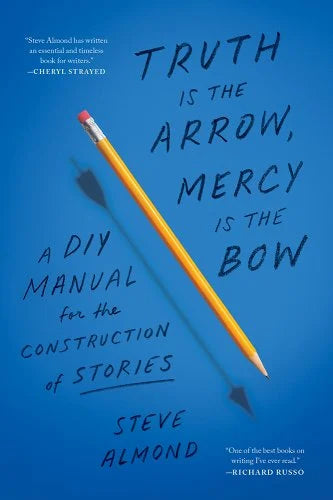

Steve Almond, TRUTH IS THE ARROW, MERCY IS THE BOW

Zibby is joined by author Steve Almond to discuss his wonderfully wise, irreverent, and inspiring new book for writers, TRUTH IS THE ARROW, MERCY IS THE BOW. Steve touches on the technical aspects of storytelling (like plot and character development) and then delves into the roots of storytelling, inspiration, and the importance of confronting inner demons, vulnerabilities, and societal expectations in the writing process. He also shares anecdotes and advice for those experiencing writer’s block, self-doubt, rejection, vulnerability, and, ultimately, creative breakthroughs.

Transcript:

Zibby: Welcome, Steve. Thank you so much for coming on Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books to discuss Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow. Congratulations. Thank you. Okay. Tell listeners about this book.

It's a DIY manual for the construction of stories, but it's really a lot more than that, I think. Talk, talk about the, the goal of the book and, um, your background as, you know, a teacher and a writer and all that.

Steve: Yeah. I, I think of this as a book about the creative process. So that has, you know, Three parts to it, or at least as I see it, there's the part that's about craft and learning the elements, which feels very intimidating, I think, to people who are early in their writing careers or who are not writing like, Oh no, it's technical plot character.

How do I do that? So there's a section that tries to speak very simply and directly to basic elements of plot. But the creative process is also about inspiration, where stories come from. So there's a section that's about where stories obsessions, our doubts, our desires. And then there's the part that for me is kind of the heart of the book, which is, okay, you know, you want to write, that's natural.

We're trying to write all the time, or at least tell stories to understand the meaning of our lives. But there are all these evil voices that rise up when we get to the keyboard that nobody talks about in your writing workshop, because we keep it private. When you get writer's block, you feel ego need and anxiety about other people judging.

The work or it's being rejected or even worse people, your beloveds, your family or friends. Feeling exposed or feeling that you've broken certain silences that you shouldn't and, you know, women in particular moms, for instance, just as an example, because I know that's a lot of your audience, like their feelings about having children and being mothers and the expectations that are placed upon them.

Are a burden and oftentimes they feel ambivalent about it, but they don't feel they can speak about it. So if they decide to go to the keyboard and say, I want to write about a time, I was driven so crazy by my kid. I couldn't stand it and had all these terrible thoughts. There are a lot of voices that rise up in them saying, you shouldn't say that.

You must never say that you'll be punished. If you say that. And I wanted to really write about all those evil voices that, that you have to, you can't make them go away. I can't make them go away, but you can slowly and incrementally allow yourself to speak about the truth as long as you're going in search of the truth with mercy.

That's why mercy is the bow.

Zibby: Got it. Um, well, you do sort of sprinkle the chapters each with different writing prompts, but you don't call them writing prompts. You have some sort of name, but I can't remember what it is.

Steve: Prompts sounds very serious in german. It's more like free rights. Yes. Free rights. Take the prepter off.

Zibby: Yes. Thank you. But I did find myself reading this book being like, Ooh, I should just sit down and do some of these. Like this would be really helpful as I procrastinate my next book. You know, I'm like, maybe I should think about like my most humiliate or like the things I don't talk about or all the different assignments.

Um, I like assignments. I feel like a lot of us, like, I don't know, people who loved school, there aren't enough assignments in this time of life. You're just like, go do whatever.

Steve: Right. Well, what you're saying is you. Understanding your own process and saying, I am a person, Zibi, who needs external expectations.

I don't view them as negative. I view them as the part of the way I get myself to the keyboard. And without that structure, I kind of feel adrift. I understand, you know, the, the big secret about my career. People say, Oh, well, you know, how'd you decide to do this, that, or the other book? And oftentimes the answer is somebody asked me, and as a former journalist, I suppose like, yes, I'll take that assignment.

Thank you for giving me some direction because otherwise. My hurricane of an ADD brain cannot focus in on the task. So, so that's good. So, you know, your process, you want some assignments. So I gave you some assignments.

Zibby: Thank you for that. You can tell that both your parents were therapists in the way that you took my comment and gave it back to me in a very

helpful way.

So thank you for that.

Steve: Well, that's probably worth mentioning. My folks were both therapists, but it's also like writing isn't therapy. No, as a veteran of therapy, therapy is pretty boring. You know, your paid help will listen to you work through all your evasions, but you know, the reader's not gonna you need to Distill down just the moments that really matter You know, this is a storyteller and writer and that's part of your work, right?

But I do think that that process is therapeutic I do think that the act of trying to step back and understand your own life or write about a series of characters who in some way or another are kind of enacting your anxieties and your yearnings and your inhibitions. All of that is like part of how we come to understand and come to peace with how we're moving through life.

Zibby: Yes, very true. Oh, I love all of that. So throughout the book, you address different pieces of the puzzle of writing. Writer's block is a big thing in here, which it is for many people, and I actually just wrote this whole novel about a woman who has such bad writer's block that she can't get her book in by the deadline, and so she decides to hand it in blank as a commentary on the publishing industry.

Steve: And That's blank. Oh, I love it.

Zibby: That's what that's about. But anyway, so I'm very familiar with that, both from a character's standpoint and, you know, myself. So, can I just read you the things that you do to avoid writing, which is all in capitals, which is hilarious, this list. Yes, please. Um, okay. Uh, you said, not having as yet established a subject, I will now proceed to a digression entitled things I do to avoid writing, an area of inquiry expansive enough to accommodate its own essay, or perhaps memoir.

One, Google myself. Two, lament photos of myself that appear on Google. Three, review my list of enemies. Four, curse the many editors who refuse to respond to my emails. Five, compose elaborately casual and nonetheless imploring emails attempting to elicit a response to my previous email. Six, urinate. Six A, ponder if I urinate too much.

Seven, recall what the peculiar fondness of middle age, my last colonoscopy, and mull whether it was appropriate for me to say to the doctor just before he put me under, aren't you going to buy me dinner first? Oh my gosh, you're so funny.

Steve: It was such a terrible moment. Oh my gosh. Just like, I am not that kind of doctor.

This is a medical procedure. I am not going to participate in your weird...

Zibby: contemplate my integrity, wander upstairs for a snack, brood over why my children have no respect for me, consider an elaborately casual and nonetheless imploring email to my children, engage my wife in some complaint related to topics 1 through 11 until such a time as she asks me to repair something. I mean that list, by the way, That's a great example of a list and one page of text that tells you so much about a person, right?

Look at what you just did there if we talk about craft and all of that. Like we know so much about you now, not only that you're funny, but all the different parts of your life and your age and your family. And I mean, it's, it's pretty brilliant when you break it down.

Steve: Well, it's not bad to take a writer's block and say, hold on, rather than hiding from it.

I'm going to build a whole book about it. Not bad.

Zibby: Good strategy.

Steve: Good strategy. And I think there's a deep lesson in that that I was trying to get out in that writer's block essay, which is we view the moments of doubt and inhibition when we are distracted and overtaken as the enemy, as something shameful.

And when, when it gets bad enough. We call it writer's block, which is, you know, the black plague of writers. And what we do is go into isolation, quarantine, and pretend it isn't happening and not speak about it publicly. And it's such an unhealthy and self punishing and counterproductive way to look at it.

You sat there and said, I've struggled, I assume, with this feeling of being blocked and doubt overtaking my capacity to make the decisions at the keyboard. And rather than hiding from it, you said, what if I actually leaned into it? And made this, you know, this anxiety and this issue central to the plot of the book.

And I feel the same way about writer's block in that essay. I realized every time I've gotten blocked, like we need to broaden our definition of block. It isn't just when you can't get to the keyboard. I've spent whole novels blocked. Where I've written these failed novels where I was like, fingers were moving.

The characters were moving through rooms, but there was no heart in it. It wasn't alive on the page. I've rewritten paragraphs hundreds of times because I don't know the next beat in the story. That's the kind of block. And even when it's gotten bad enough that I couldn't get to the keyboard. It stripped me of a certain vanity that was saying, Oh, you know, you should be writing the great American novel, which I'm not capable of writing.

Unfortunately, I can write a funny list, but I can't write the great American novel. That block was my ally. It stripped away that vanity, that idea about myself. And I was able to ask a much more useful question, which is. What do I want to write? What, what story will get me back to the keyboard and feel like the American compulsion is always to try to achieve.

And, you know, you always have to do it at the highest level. And I think actually the way that people contend with when they feel blocked is just the opposite. They lower the expectations. I always say when people feel blocked. Just set the expectations as low as possible. Only get to the keyboard for five minutes.

Fine. Start there because otherwise that negative feedback loop starts up and you know, the thing you're afraid of and your inability to face it becomes another reason to feel ashamed and makes it. That much harder to do with it.

Zibby: I mean, like we call it writer's block, but it's essentially, you know, writing anxiety.

That's really all it is. It's just dealing with the anxiety of, of writing. And that's why it's funny when you write it down because a lot of writers share this anxiety because it's also what makes us question things and observe things. And, and. You know, it's that interior monologue, which can be used for good and for bad, right?

It can work with us and against us. So it's, you know, we could almost use like CBT tools of, you know, wrestling with the demons, if you will.

Steve: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I, I think we think of that stuff as our neuroses and our anxieties and therefore something that's pathological and that we should hide away. And like, when we come to the keyboard, we're just strapped in and ready to go, but I don't know about your experience.

That's not my experience. I didn't want to write a craft book that was like, Oh, the wise professor will hold forth. That's not how I feel. I feel like a mess. And that is not an exaggeration. That's literally all the gymnastics I'll go through before I try to even make a decision at the keyboard, which I'm eventually going to rewrite anyway and later cut, you know, like if people knew how inefficient our process was, they would be so deeply disappointed in us.

Yeah. And rather than allow them to be. I'm going to say that's our process. You know, it's really, really hard to sit alone in a room and make decisions. And you're choked by doubt the whole time. And many of those decisions just. Weren't the best ones and the more we can detach from our ego around. I am a writer capital w or am I a writer yet?

And the more we can just say you're just trying to make decisions And you're probably going to get them wrong a lot of the time where you could get them writer then the less we Get into the opera of self doubt of like everything's at stake for me, like surrender is a big part of this surrender that you are going to have phases in your writing career and in your writing session where you just get distracted or your doubt overtakes your, your sense of self belief.

Zibby: Wow. I love that. Thank you.

Steve: Well, you know what's interesting? I'm going to find blank and I'm going to read it.

Zibby: I'll send it to you. I'll send it to you.

Steve: That would be awesome. Yeah. I'll send you a copy. When people, I don't know about you, but when people post stuff on social media that, and I know I get it, we're all being told to like constantly market ourselves, especially if trying to sell something as inconvenient as a book.

So I get it. I do the same thing. But basically the culture says like trumpet your successes. And never write about your failures. And so we all carry around our little vault of failures in silence. And we sort of look at that as a mark against us. Rather than saying, okay, this is a natural, inevitable part of the process when I'm writing well, which is rarely, I'm not learning anything from it.

But when I, when I fail, I can actually look back at that and say, oh, I see. I didn't have a narrator on duty. Oh, I see. There wasn't a chain of consequence. I hadn't cleaved my crazy chain of associations to a chain of consequence, which would have created rising action. I actually I'm learning from all that awful prose that I was writing.

I think we have this feeling of trying to hide it away. And all we see in public are the published authors, the Lori Moore's, you know, for me, she was like my lodestar and I was like, Oh my God, she's never written a bum sentence in her life. Nonsense. It's just that we see the little, Right. Portion of decisions that, you know, move out into the world.

So we believe, Oh yeah, she's always just pooping gold. And it's like, Nuh uh.

Zibby: Yeah. I posted a video of all my, me reading all of my rejection letters from 2004. It's on my website somewhere. I have to, I'll send it to you also, but I saved them all, you know, they were typed back in the day. You know, I had sent in my, you know, Kinko's box of, Pages and gotten rejection after rejection for my first novel and it's not easy and I was embarrassed for so long until I realized having talked to so many people like you and all these other amazing authors that it is not a straight line and so many people get rejected and actually that's part of it.

It's actually quite rare for someone to have their first book just go and then you think about it like art. I mean if there was an artist, right, you wouldn't expect them to have it all be perfect.

Steve: Posting that. Those videos of your rejection letters, one, gave people incredible hope, and it was funny for them the same way that list you read of mine is funny, because it's true, and because you're brave about telling the truth.

So a lot of people I'm sure told you, thank you for doing that. It gives me, I'm no longer alone with that myself. And that's why I feel like the social media model, which is just built to make people dissatisfied and miserable anyway, so that they can be sold stuff. But it's so destructive. I want to see the version of Instagram that isn't the perfect sunset with the family all smiling.

I want to see like five seconds later when it all goes to hell, I'm more interested in people's. Failures and struggles because that I can participate in, you know, their success. I like good, good for you, but I want to see how you got there and know that it was difficult. And if there were a lot of rejections along the way, because then I can feel less ashamed of the real process.

And I don't think there's, I mean, maybe there's some people who just out of the gate, you know, succeed and they have that talent and they're Mozart or whatever. And okay. Like, I'm glad I lived at a time that I could listen to Mozart. But I'm not Mozart, I'm schlepping along and that's why I wanted to write the book as kind of a schlepper, not as the wise professor, but as the writer who's struggling and failing and just trying to learn from the failures.

Zibby: You were so self defecating at the beginning. I was like, okay, is this going to be, is he going to give me any good advice? I'm just kidding.

Steve: Maybe I'm disqualifying. Yeah.

I mean, I'm not trying to play dumb, but I'm not, I'm also not, I'm also trying to make clear that. Doubt is with you always and nobody gets past it and we should stop believing that you should get past it because it's actually really important.

It's like a furnace that fuels you. And the same Zibi that's reading these rejection letters and sort of marveling at how much harder it is than she thought is going to have to show the same self deprecation or just self awareness or acceptance of the weak, vulnerable, unsuccessful parts of herself that allows you to then take a writing block and say, actually, this is a story.

If I'm less cruel to myself and less ashamed about it, this is the story. Which readers will really want to participate in because they have the same story. It doesn't matter whether they're writers, they could be painters or filmmakers or musicians. It's the creative process.

Zibby: Yes. Actually, I've been thinking about that more and more because our expectations of if we were to put writers in the artist category more than we are typically thought of as like, you know, uh, I don't know, less in the financial modeling, you know, like output job and more in the like, yeah, content and more in the like, I'm, doing a painting in my studio, like you would never expect someone with their paints and brushes to like get up to the canvas and make it perfect, right?

Of course they would repaint certain areas. We would expect that and that's part of it. So we should give ourselves the same grace when we have a manuscript. It's, it's the same brushstrokes. It's just, we have to do it differently. It's the same keys that could do a model, you know, different, different tools, same tools, different art.

Steve: Yeah. And the same. In sort of for writers, I think there's this idea when sometimes people will come up to me, not often, but like, you know, after reading, somebody might come up and say, you know, I'm not a writer, but I've always had, you know, I have this great idea for a novel. I don't know if this happens to you and always have the same internal thought, which sometimes I have the good grace not to say to them, but there's like a part of me that's like, cool, why don't we meet in a year and show me your novel?

Like they just have this thought of like, yeah, it's just about creativity and letting it flow and Kerouac and his one, you know, reeling butcher paper, you know, typewriter session. And I'm like, No, it's so disappointing and so incremental and so stop and start and so wander off to the kitchen to catch or eat something and then feel shame about it and think about your colonoscopy and like, ugh, that process is so human and messy and we, we, even as writers.

We flatten that story out into, Hey, after years of work, here it is. My, my managerships going into the world, like celebrate that. And I'm like, all right, I definitely want to celebrate that. But like, tell me about all the struggles along the way, because I'm in the middle of them.

Zibby: Yep. Totally, totally agree.

I feel like that's when people relate to me the most is when I'm saying like, things like this morning when I thought the kids had the bus and the bus didn't show up and I forgot to check the WhatsApp. And so, you know, my husband had to get out of his pajamas and like go to school and cause I had the podcast and like, you And I'm like, I missed the bus again, you know, messed up the bus. You know, it's like, it's not always so pretty.

Steve: It's almost never so pretty.

Zibby: Yes. Exactlty.

Steve: Why I think we carry this fantasy of If we can represent the digital version of our lives, that is so pretty, then maybe the world will believe like, we're always telling these two stories, the story about who we want the world to believe we are and the story of who we knew, know ourselves to be right.

So he's like this bestselling author and she does a podcast, their library looks great. And so, right. That's one story to me anyway, right? I'm seeing that story. And then you're saying, ah, no, no, no, everything's a mess and I need an assignment and I'm blocked a lot of the time and it feels like chaos. And, you know, I had to fight through a lot of rejection to even have my provisional successes, et cetera.

And that is the real story. And then to me, where. What's fascinating is that's where most good stories happen. The central danger is self revelation is the story of who we think ourselves to be colliding with who we know ourselves to be, or who the world tells us we are. I'm thinking of Emma, Jane Austen, right?

Emma is this entitled privileged person who's sweet and smart and charming and handsome, young and rich, but she's doesn't realize that her meddling and her entitlement is really destructive and the novel tells her that and she learns that lesson like right in front of us. And so I, I feel like that's the central danger is self revelation and, and we as.

As authors have to experience those self revelations and accept them like you're saying, I know I'm wanting to appear put together, but my life feels chaotic and I feel guilty and I've screwed this up and I've messed that up and I'm barely keeping it on the rails. And to me, like, that's the superpower that writers have.

We can outlast our doubt. We can admit to it and manage it.

Zibby: I love that. This is great. I'm going to lean into this on social. You also talk in the book too about finding your obsessions, things you're obsessed with, and as a kid what you're obsessed with, and like just sort of going to that deepest part of you where like you don't know why, but like you can't stop thinking about, I don't know, Moose Tracks ice cream and why it was discontinued and, you know, blah, blah, blah.

Like all these things that you're just like, I don't know why my mind goes there. But turns out usually someone else's mind is going somewhere similar or there too. So I loved that advice in the book as well.

Steve: Yeah, I think the way I would look at it is the reader really wants to know two things. They want to know all sorts of things.

Where are we and what's at stake and so forth. But they want to know who to care about and what that person cares about. And that's what hooks them into story. And so if I say, uh, you, I'm, I'm the author, Steve Allman, and I'm heartbroken that the Caravelle candy bar was discontinued and I've never understood it.

And I am the reader's like, okay, well, let's go on that journey and figure out how that happened. Right. You know, I don't think of us as. Finding obsessions. I think of us as really admitting to the obsessions that are already in there. We're born into obsession You know, you have kids, you know, they're obsessive in their desires They're obsessive in their phobias and it's kind of socialized out of them because it's disruptive to feel so much And to care so much about something but that doesn't make them go away.

That just makes And go underground and then they're sprinkled with that force of suppression. So for me, like what got me out of my most sustained hurdle, uh, when I, you know, have a novel that is basically worked on for three years and then it's rejected in 40 seconds, rightfully by my agent, what got me out of that block was.

The obsession that it had as a kid with candy and chocolate and realizing that that's the one thing that's getting me out of bed, a good piece of chocolate. It's the only thing that makes me feel alive and interested in the world. And by the way, that feeling's pretty ancient as a kid. Candy was the one dependable pleasure in a childhood that was sometimes really sad and lonely.

And reconnecting to that felt to me, to the guy who was trying to be a young writer and write a great novel, like, Oh, what a silly, stupid piece of pop culture nonsense I'm writing. But to readers who have their own obsessions and who have hidden them away, it was like a great relief. Oh, I found somebody who feels so urgent.

And the moment I got into a candy factory. The depression that I was in, not just writer's block, but depression lifted and the elevators smelled like Halloween. And there was a conveyor belt with, you know, marshmallow bunnies, shimmering being covered in a wave, a little curtain of chocolate and I was like, Oh my God, I'm alive again.

I'm paying attention to the world and I'm enthralled by it. And that's really what you're going for. I feel like as a writer, the moments of grace and, Creativity and sublimation are when you're more interested in the story than whether you're telling it well. You're not performing trying to say, well, aren't I sensitive?

Aren't I smart or whatever? You're just so into it that the story itself is what's pulling you forward, not your attempt to perform, but really being a storyteller in any language you're using is serving just to tell that story and the reader can pick up on it.

They don't want, it's not the, what you're writing about.

It's the quality of attention that you're giving to that subject, whether it's candy bars or writer's block or oranges or some football team that you love or whatever it is.

Zibby: Well, there's so much more to your story, your, you know, confessions about this sort of traumatic moment. With your brother and the baseball bat later in life and your memory, his memory, you know, some very painful moments with your mom and before she passes away and talking about that and a lot of the hurt.

And anyway, I really. appreciated the backstory of you interspersed with all the many quotes from contemporary literature, which is also great because there's a lot, there are a lot of books that quote from the classics only. And you were like, no, no, this is, you know, people I've had on my podcast, they're quoted here.

I'm like, oh, this is amazing. So I feel like it works so well to have this contemporary look over what's to come. Being done well and great inspiring examples and then your own story, which just shows us that the more you put your heart on your sleeve, the more you can connect with any sort of advice or whatever.

The main takeaway really, really is.

Steve: Yeah, I really wanted to include contemporary literature, just books. If I read, like I read Memorial Drive and it just captured me, or I read a burning Megha Majumdar novel and I absolutely got obsessed with them. And I think it's important for writers and artists to be like, if you love something, then try to understand the mechanisms of its enthrallment.

It's not a mystery. They made a whole bunch of really good decisions about narration and where to start the story and the language they chose. Study them, not like it's a holy text, but like it's holy to you. And they did it somehow. And it's not a mystery. You can try, you know, it requires a different kind of reading.

Cause you're not just taken up by the story. You're partly trying to understand as a writer. Oh, I see. You know, Natasha Trethewey starts with this photo of her mom, but actually we know from the first line of the story that her mom is going to be killed. The last photograph has taken of her at the crime scene.

Oh my God. But notice how that. Makes us immediately know that there's a dangerous upsetting story here, and we know that that story from the very first sentence is going to investigate that death, but then we move to this second photo that the mom constructs, and you know, she's trying to put forward a vision of herself finally having escaped the abusive relationship she's been in for so long, and like, you Those two timelines and what they tell us about how the story is going to be told.

And it's just heartbreaking and remarkable. And I wanted to write a book that said, look at somebody doing it really well. I don't want to just set out ideas in the abstract. Here are people executing it. Here's how they did it. We can understand this. It's not mystical and it's not purely technical either, but it is good decision making.

The same thing is true of including like the story is some of the stories from my life. If I'm going to tell the reader, hey, you have to tell the unbearable story. You have to forgive yourself. You have to go in search of mercy and understanding and I kind of should model that, right?

Like, I think a craft book that's just about craft is Dry toast, you know, you've got to like put some, some of the hot butter of your own mess onto it.

At least I felt in this book, not so it becomes the memoir or solipsistic, but just to model for the reader, this is what I mean. You have to put some skin in the game.

Zibby: Yep. Oh, my gosh. I love it. Well, there's so much I didn't even get to because I could talk to you literally all day about this book and writing and everything.

Steve: Oh, I wish you would.

Zibby: I really would. I really could.

Steve: It's still fun.

Zibby: But I hope to meet you in person someday and thank you so much for this book and all the advice and, and my new list of assignments. So thanks.

Steve: Yeah. Well, listen, will you send me blank? And then I'll send you my colonoscopy results and we'll call ourselves even.

Zibby: I'm going to make myself a note so I don't forget. Okay. Yes. I'm going to send you it today.

Steve: Awesome.

Zibby: Thank you so much for coming on. I really appreciate it.

Steve: It was a total pleasure. Thanks.

Steve Almond, TRUTH IS THE ARROW, MERCY IS THE BOW

Purchase your copy on Bookshop!

Share, rate, & review the podcast, and follow Zibby on Instagram @zibbyowens