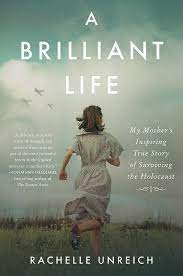

Rachelle Unreich, A BRILLIANT LIFE: My Mother's Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust

Zibby speaks to journalist Rachelle Unreich about A BRILLIANT LIFE: My Mother’s Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust, a delicate and evocative family history built from the interviews she conducted with her 89-year-old mother, Mira, before she died of cancer. Rachelle shares what it was like to uncover both the horrors of the Holocaust and her mother’s incredible resilience and optimism. She highlights her mother’s unwavering faith in humanity and the lessons she imparted about finding hope in dark times. Finally, she reflects on the painstaking process of writing this book during the pandemic lockdown and then touches on the themes of intergenerational strength and mother-daughter bonds.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Rachelle. Thank you so much for coming on "Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books" to discuss your absolutely beautiful, heartbreaking, inspiring, all of it, amazing book, A Brilliant Life: My Mother's Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust. Thank you.

Rachelle Unreich: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me. I'm really excited.

Zibby: I must say you have quite a fan club. I feel like so many people we have in common have reached out to say, oh, yay, I'm so glad you're having her, when I posted the picture. Lots of love and support for you in the community already, so that's wonderful.

Rachelle: And all the way from Australia, which is where I am.

Zibby: I know. Crazy. You know Jane Green too, right? She was one of your --

Rachelle: -- I do. I met her now husband when I was working at FAO Schwarz as a student at university many moons ago in the eighties.

Zibby: The world is a crazy place, which of course, is one of the themes of the book, all these coincidences and reasons things happen, perhaps and perhaps not, and all of that. Why don't you tell listeners a little bit about the backdrop of the book and how you started interviewing Mira? Tell the whole thing.

Rachelle: I started interviewing my mother six months before she passed away in 2016, was when I did the interviews. Even though I'm a journalist, I didn't interview her to get material for a book. I did it because she was suffering with cancer. I wanted to distract her from her illness. I knew she’d been a Holocaust survivor. She had entered the first of four concentration camps when she was just seventeen years old, including Auschwitz. It wasn't so much that I wanted to know what had happened to her because I had some grasp of that, but rather, how did she survive and live with this incredible joy and buoyancy afterwards? She was a really remarkable person. One of the things she said which always struck me was when she was interviewed in a testimony by the Melbourne Holocaust Museum. They asked her at the end of this testimony where she just went through a litany of horrors -- so many people around her had been killed. She’d just seen so much brutality. At the end, they said, "Is there anything you want to add? Anything you've learned?" She said, "In the Holocaust, I learned about the goodness of people."

That became the center point of this book, how she had this attitude and what her lessons of faith really meant. I felt she had faith in humanity, in the prospect of a better tomorrow, in herself, in the universe. I wrote this book during another bleak time, in COVID. We were stuck in lockdowns in Melbourne, Australia. This was lockdown number six. I just really felt that she had lessons that were valuable to share, that the way she lived her life could be a template for others. As you remarked, there was so much in this that wasn't just about the Holocaust. I wanted to do a really accurate historical record of what happened to her. It was really important that I got that right. I also wanted to talk about how she lived with such creativity, so much independence. It's really a love letter to her. It's about mothers and daughters and that bond that cannot be broken, even with death. I felt so much grief when I was losing her and when she did die. I just went to words to try to write myself out of that. Along that, as you mentioned, there are all these strange things that happened around her that I don't really name or identify properly in the book. It's for the reader to decide. I really deal with concepts of fate and coincidence and luck and serendipity and try to work out how that all fit in with her.

Zibby: I like that because it leaves you feeling quite hopeful. I feel like when you hear stories like the psychic who predicted you were going to get in the accident and then your mom saying that she was convinced your grandparents had saved your life that day, it makes me feel personally less anxious about the thought of dying myself or that all my loved ones who are dying, that there is still this huge other piece of it that we just don't understand. That provides me, at least, with some comfort. I don't know if it does to you as well.

Rachelle: Yeah. To be honest, I started writing this book -- even though it had been percolating in my brain for as long as I've been a writer, which is decades, the catalyst was that during lockdown, I kept going for a walk with my neighbor Diana. On the very first day of lockdown, she’d received terrible news. Her husband had been diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor. She kept wanting, on these walks, to hear about Mira. I realized it was partly for her to realize that you could suffer something incredibly beyond challenging, something so difficult and traumatic that you didn't know if you could get through. Mira's story showed you that you could not just get through, you could actually flourish. She is Catholic. There was this idea for her, too, that the world was bigger than something just us here and now. It felt really comforting for her too.

Zibby: Do you believe that your grandparents saved you? I know this is such a minor -- not minor. It sounds like it was a horrific injury for you. Do you believe in that? Then the psychic said you were supposed to have died that day.

Rachelle: I don't know if the psychic was right, but I believe in my grandparents more than the psychic. When that happened, I was in an accident. My mother had had a dream where she knew exactly where the accident had happened. I don't know how to explain that otherwise. I'm sure there are other reasons behind that. I became a person of faith myself, partly because of my mother's stories. There was this really pivotal one, as you'll know, that happened towards the end of the war where after eight months -- she’d been in these series of camps, in Płaszów, in Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and Neustadt-Glewe. She was seventeen years old when she went in. By the time this eight months had passed, she had deteriorated so much. She was so skeletal. She was what they would've called a Muselmann where you describe the walking dead. The term also indicates when some of the light has been lost too. She had been really depleted. She couldn't stand any longer. She was so worn and so thin that she was only lying in the barracks. She couldn't go to the appellplatz, the daily roll call. Women would stand in her place trying to call out her name. She said that every tooth was wobbling in her mouth. Her gums were filled with puss. She’d reached the point where she just didn't know what lie ahead of her. She knew that many of her family members had been killed, include her mother. She just reached the point where she believed her mother was in another realm, and she wanted to be with her again.

On this one particular night, she went to bed, and she prayed. She prayed to God fervently and asked him, "Please take me in my sleep. I'm ready to go. I'm ready to be with my mother again." That night, she had a really vivid dream. In that, her mother, Genya, came to her and started washing her body with a washcloth with long strokes. Then she had a bowl of soup. She fed her soup spoonful by spoonful. Before the end of the dream, she said to Mira, "Mira, I want you to hold on until your birthday. On your birthday, I'll come and save you." When my mother woke up in the morning -- surprise, because she really thought she might die in the night -- she really felt like it was a dream like no other. She really felt like Genya had crossed over to be with her because she felt different. Even her body felt slightly more sustained. She had a tiny bit more strength as if she really had been fed.

She thought to herself, I made a promise to my mother. My mother asked me to hang on until my birthday. My birthday is four days away. I'm going to keep that promise. I know that if the end of the four days comes and goes and nothing's happened, if I'm still here, I'll be able to let myself go. This time, it'll be for good. On the day of her eighteenth birthday, she was finally liberated. I grew up with that story. She told it countless times. I still often feel teary when I tell it. Of course, you can explain it as a massive coincidence, but there were so many things like that that happened to her that I just believe in her. I believe in her faith. I believe in the strength of a parent's love for their child. Like you said, I feel hopeful. None of us will be able to prove it, but it's really what guided me. Even writing that book, I have to say that I've never written like this in my life. I wrote the first draft in six weeks. It was impossible to believe anything but the fact that my mother's hand was underneath me because those words flew off the page. Writing for thirty-seven years, that had never happened before.

Zibby: It's almost like you were transcribing. You have all these stories. It's like a history. Not a history because obviously, there's two timelines. There's your own thoughts and everything, all of the knowledge that you have of what happened with her even before the war and what her family was like and all these things and the things that you didn't ever find out but you imagined. Had you already completed all of that research before the six weeks? Did you know some of the answers and details?

Rachelle: I had all the transcripts of her interviews. That included her Holocaust testimonies and my interviews with her, a whole series before she died where I really did find out not just what her life was like before the war in Czechoslovakia, which you often don't see in Holocaust stories, from the beginning, her story, this idyllic little village where her family was filled with love and laughter and culture. That really informed her later on. Then I wanted to talk about afterwards, the life she led and what she was like as a parent and what she was like to me. I actually just started writing and using her transcripts. That was how I began. Every time it kind of felt like I needed a switch or it felt heavy for the reader, I would insert something of myself in here or a story that made sense. I did that for two reasons. One was I wanted a bit of a break from the linear retelling of my mother's story, but I also wanted to make sure that readers didn't get too desensitized to the horrors. When you read a Holocaust story, there are one thing after the other, after the other, after the other. When you get to enough of them, I think your brain switches off. I wanted to make sure that each thing hit the reader fresh because I don't want a romantic retelling of the Holocaust. I want an actual telling of the Holocaust. It was so important to me to get the facts straight. There's nothing invented in this book. There's no emotion that I made up. There's no conversation I invented. Everything that she said came from her mouth in the retelling, or that her parents said. If I didn't have that, that didn't go in. After the six weeks when I wrote the first draft, then over the next two years, I went to all the Holocaust museums and historians and scholars I could think of. I searched for descendants. I went through every archive that I could and got together all the rest of the information, tried to verify every single thing she said so that nobody could one day point a finger and say, that's not true.

Zibby: Oh, my gosh. One theme in your book is that at first, no one would believe people who had seen it and came back to report it because it was so horrible. People, had they all believed and reacted, perhaps things could have unfolded differently. Yet they didn't. Knowing all of this and then applying it to today, what do we believe? What do we hear? How much credence do we give to different stories? All of that. Where do we take all of this? For me, I read it, and I'm like, okay, my ears are open. Anything I hear must be true. Where do you take all of this? What do we do with all of this now?

Rachelle: To me, it really is the idea that history can easily repeat. You see that from the beginning because the Holocaust didn't start with monsters throwing people into pits. It started with stereotypes being perpetuated and hatred being allowed to go unchecked and people, good people even, not standing up for what was right and what they could see, but going with, often, the majority instead. You see that playing out today. You see these stereotypes of Jewish people, of all these different elements being written about. You see the majority kind of coming together with one belief. You see a lack of critical thinking that happened then. To me, my mother really emphasized humanity. I think that is such a key message today. It's really important for everyone not to see everyone else as others. We are all humanity. We all have to remember that and recognize that and not be so quick to put people into one section and label them, to really try and reach an understanding and to lead with, not hatred, to lead with what the end goal should be, which should be, in the current day, we want eventual peace. We want people to live happy lives. Everyone. We want all innocent people to live happy, fulfilled lives.

Zibby: Wow. It's inspiring and, as I said, horrifying. There were some images too -- I have read so many, as most good Jewish girls do, many Hebrew school classes and then my own interest as I've gotten older and in college and just all the books that I read and movies and everything. There was one line in here where you talked about the people when they were thrown into the pits, or the invalids. They were thrown into these burning pits and then covered with dirt. Someone said that the earth would move for days. Oh, my gosh, I just can't get it out of my head. It's so awful. It's just so awful.

Rachelle: That was something my mother had been told by her cousin because that is how her mother was murdered. It is, it's those images. My mother herself worked burying -- when it came time for the Nazis to try and liquidate the camps and they were trying to cover up their crimes, they were exhuming the bodies. People like her were covering it back up. They would find terrible things in those pits left behind. Even though I know her story and even though I knew her, I still cannot completely understand that she had that past and that she managed to live the life she did. In Australia, we had the largest Holocaust group immigrate to Australia outside of Israel per capita. We had an enormous amount of Holocaust survivors. I only realized when I was writing this book how many of her clique, of her friends were survivors. You just wouldn't have known it. My memories are of these gaggle of people coming over in throngs to your house and playing these very exuberant games of cards and laughing. The women were there in big bouffant hairdos. The men suntanned. Just so much merriment among them. They were fabulous to be around.

Zibby: Wow. I feel like most, as you well know, most children of Holocaust survivors in particular grow up with a unique set of traumatic responses being the keeper of this information and all of that. Have you been in touch with other children of survivors to contrast your experience? I wonder how the ripples of all these different family trees and different responses then affect the Jewish community forever.

Rachelle: When I lived in Los Angeles, which I did for a time, I once went to a meeting which were of people like me, those descendants. I couldn't quite relate to them because, first of all, they were quite a bit older. My mother had me later in life. She herself was so young as a survivor. They were two decades older than me. They spoke of parents who were really scared, who were overprotective, who sometimes hoarded food. That's not all survivors, but those were those survivors. That, I didn't relate to. I've got lots of friends in Australia whose parents absolutely refuse to speak about what they went through and can't. If they even touch on it, they have nightmares. They're disturbed for weeks and weeks. The children, of course, don't want to do this to them. Somehow, my mother managed to be able to tell her story quite often, whenever she was asked, without retraumatizing herself. I often feel like rather than intergenerational trauma, I had intergenerational strength or even joy.

It's funny, the other day, it did occur to me that some of it bleeds through. I grew up in this really magical house, a crumbling Victorian house that was divided into apartments. We lived in one of those apartments. Somebody came through the house recently, which we still have, and said, "Wow, all these rooms here, these old rooms, you must have, as a child, imagined all these incredible things. It must have planted the seeds for a book." I thought, the only imagination I had about the house was imagining secret doorways in the floor where I could hide and underground tunnels in case anything went wrong. I realized how much was informed by that background. That aside, I don't feel like it really penetrated me.

Zibby: Are you also allergic to hay?

Rachelle: I am.

Zibby: Are you?

Rachelle: I really am. I went to some hay bale, maybe it was a Halloween-y thing, once. I just had to leave. I was sneezing so much with my kids.

Zibby: You don't think about that. The scene with your mother and being allergic -- my daughter is allergic to everything, including hay. I was thinking, oh, my gosh, all the sneezing if she was trying to hide.

Rachelle: It reminds you, my mother's story and any survivor's story, how much luck, how many good turns were required in order to be saved. That's really true of any survivor. You survived because you were physically able to. You survived, probably, because you were mentally able to. You survived because so many series of things happened all along the way that saved you, and not just one and not just two and not just ten. There were one after the other. Statistically, it was, you went into camp, and you didn't usually come out.

Zibby: I feel like you really captured the indecision -- not indecision, but it was impossible to know what to do then, even at the beginning with all of the aunts and uncles. Do we go here? Do we go there? I could just imagine within a family, what do you think? Should we report? Should we hide? Changing their minds. You just don't know. It seems like one decision after another, and then there's your whole life, obviously, but huge ramifications. What has been the response? Your book has come out during this crazy time in history now. How has this been for you? How has the anti-Semitism been, if at all, towards you and the book? What has it been like?

Rachelle: In the last few pages of the book I actually write, "I don't know if I'll ever see hatred like this in my lifetime." Then of course, by the time the book was actually out there, that hatred had happened. In Australia, it came out three weeks after October the 7th. At first, I thought, I don't know if I can actually even publicize this book because how can we talk about an old horror when there is a fresh horror to deal with every day? It felt really hard. I realized once it was out that people wanted to talk about it. I think they have found hope through my mother's story, which has been incredible, that it's been somewhat uplifting for them. It is difficult. In Australia, it feels really difficult. In Melbourne, it has felt very difficult. It's hard because my parents came to this country and absolutely loved it from the beginning.

I take heart in the fact that I see so many Australians standing up against anti-Semitism. My mother was saved and helped by not just Jewish people, but so many non-Jewish people, from a Greek Orthodox priest who converted her, to a Belgian officer after the war who fed her when she was really malnourished. I look at people around me. I see strangers posting on LinkedIn. I see people in Melbourne's community just speaking up. I think the world has changed since the wartime where people are not just sitting there silently. They are being vocal. I've met with politicians. I've met a real community of leaders looking to effect change. In Australia, they've just passed legislation that has helped some of the hate online that people here have been experiencing. I like to believe that the world has changed somewhat. I see both. If you're online, it seems like a vortex of hate. I think that's a little bit of an echo chamber. I don't think that’s what the world feels like. I feel safe in Australia. I do feel, ultimately, that this is still an incredible place to be a Jewish person.

Zibby: I know you said a lot of people came over, second to Israel. How big is the Jewish community today? Is it still one of the largest percentages? I've never actually looked at that statistic.

Rachelle: I'm really terrible with numbers. I'll have to look that up. It is a really vibrant community here. We've got every kind of strata of Judaism. I go to a modern orthodox synagogue. There are plenty. There are plenty of reform synagogues and plenty of ultra-orthodox synagogues. I'm scared to say a number.

Zibby: Okay, no. I was just curious. What advice do you have for aspiring authors?

Rachelle: Mine is a real second-chance story because I started writing this at fifty-five. I published this at fifty-seven. When I wrote it, I had really told myself for years, as much as I wanted to write it, I wasn't sure I could write a book. I tried. I was reading what other people do. They plan their books. I tried to plan it. That was terrible. I tried to do the Stephen King mode of writing a certain amount every day. That didn't really work for me. What I realized was I shouldn't have underestimated myself. I thought that my manuscript, if I ever wrote one, would end up in a dusty drawer and never see the light of day. In fact, within three weeks of writing it, I got an agent. That was through a bit of serendipity as well. I looked on LinkedIn and thought, maybe I'm already friends with an agent, and I was. She was born on my mother's birthday, no less.

Then it ended up being part of an imprint auction in Australia, being sold. It got bought by HarperCollins in a preempt in America and Canada. It sold in the UK to Black & White Publishing. It's in South Africa with Pan Macmillan. It's about to have its first translation in Europe. It's funny because I went to one of those publishers, and he said, "Why haven't you written a book before now?" I said, "I didn't think I could." He said, "Who told you that?" I said, "Well, I told me that." That was a thing. When I was younger, anyone who said something critical about my more creative writing, I took it on board and just felt like I was okay in a safe place of journalism. It really wasn't until I got quite desperate in COVID where the world was closing up and articles were closing up that I almost felt that I had no choice, that this was the time. I just plowed through. It really is putting it on the page and just doing one thing after the other. Just don't second-guess yourself.

Zibby: I don't believe you're the age that you say you are. You look impossibly young. Not just look. Seem. Feel. Speak. I don't know. You have this very youthful exuberance to you. Maybe that's the part of your mom, that very hopeful --

Rachelle: -- She was incredible. She was nearly ninety when she passed away, and barely a wrinkle on her face, I've got to say. She was always cracking a joke. I still really miss my daily phone calls with her. I'd call her on the way to school drop-off. She would answer the phone as if I'd just been in Antarctica for six months incommunicado. She’d say, "Hello, my darling daughter

Zibby: It's like my puppy dog.

Rachelle: I really appreciate that. You're a part of this whole dream of me manifesting because I was really hoping to speak to you. My publisher always says to me when I get worried, she says, "Just believe in the magic of Mira." I have to say, I kind of do.

Zibby: I think that should be on a T-shirt. Believing in the magic of Mira. Thank you. Thank you for sharing Mira with the rest of us.

Rachelle: Thank you so much, Zibby.

Zibby: Bye, Rachelle.

Rachelle: Bye.

A BRILLIANT LIFE: My Mother's Inspiring True Story of Surviving the Holocaust by Rachelle Unreich

Purchase your copy on Bookshop!

Share, rate, & review the podcast, and follow Zibby on Instagram @zibbyowens