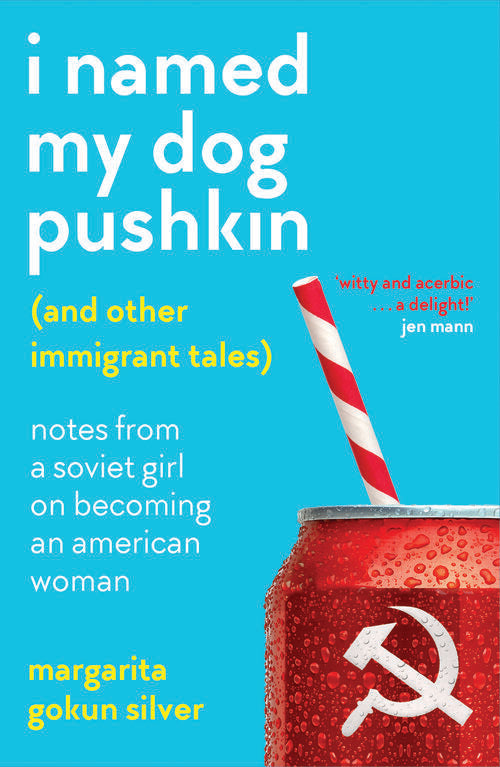

Margarita Gokun Silver, I NAMED MY DOG PUSHKIN

Zibby is joined by writer and journalist Margarita Gokun Silver to talk about her collection of essays, I Named My Dog Pushkin (And Other Immigrant Tales), which follows her journey from growing up in the Soviet Union to America. The two discuss the role Judaism played in Margarita’s upbringing and family history in the USSR, how their time at Yale overlapped by a few years, and what efforts Margarita has made to parent her daughter differently than her parents raised her. Margarita also shares the heartbreaking news of her husband’s passing and how this book stands as a testament to his life as well as her own.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Margarita. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books” to discuss I Named My Dog Pushkin (And Other Immigrant Tales): Notes from a Soviet Girl on Becoming an American Woman.

Margarita Gokun Silver: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Zibby: It’s my pleasure. In the book, of course, we realize that your name really was Rita and that it was supposed to be Rivka. Then it went to Rita. Now even your parents refuse to call you Margarita.

Margarita: That is correct, yep. They still call me Rita.

Zibby: Your collection of essays was a really funny, smart look at immigrating from the USSR and all of the things that come along with it. One of the most interesting things from the beginning at least was when you talked about when people would ask you if you were Russian. You would say, no, I’m from Russia. As a Jew growing up in USSR, you never felt like that was actually your homeland because of the way they had made you feel. Talk to me a little bit about that.

Margarita: To be in Russian in the USSR meant to have the Russian ethnicity. You weren’t just allowed to have Russian ethnicity if you didn’t inherit it from your parents. If you were of Jewish ethnicity — in Russian, they called it natsional’nost’, which would say nationality, in a way, if you translated directly into English — then you were Jewish. In your passport, in your school paperwork, in the teacher’s journal, everywhere, they would write you out as Jewish. You weren’t allowed to be Russian. When I landed in the US, suddenly, I was Russian. It was just so bizarre to my ears. I knew that I could never claim that title. I never wanted to claim that title because I wasn’t good enough to claim that title when I lived in the USSR, and so I kept correcting people. That stopped years down the road because it got tiring, but I did keep correcting people because I was not Russian and could never be.

Zibby: Then when you came here, you said there was this one scene in school where they called you a Jewess. You didn’t even know what that meant. You felt like there was a sense of difference right away, and anti-Semitism, that you confronted. Tell me more about that.

Margarita: I grew up in a very assimilated Soviet Jewish family. My parents were engineers. My grandparents were engineers. One of my grandmothers was a doctor. Nobody really practiced anything or knew anything about Judaism except for my grandfather who still remembered something from the olden days. No one told me I was Jewish in my family because atheism was the state religion. We just didn’t think of Judaism as a religion. We thought of being Jewish as something, again, you inherited through your family. Nobody talked to me about it in my family probably because they figured that was not a good topic to unload on a nine-year-old because of so much baggage that came with it. One day at school, my classmates decided to find out what we got for either a math test or some other test. That was in the teacher’s journal, so they snuck into the teacher’s journal when the teacher was away. You open the journal and one of the first pages is the information about the pupil. You have the parents’ names and the phone numbers and the address. Right there, I think even in the second column, you have your ethnicity. Of course, everybody was curious. They went down the list. I was the only Jewish child in class. Of course, immediately, fingers pointing. Even though I didn’t know that it was inherently not a good thing to be in the Soviet Union, the way children treat you, you see immediately, that is not a good thing. I just kind of, okay, something is not good here. I’m being othered, even though that language was never part of my vocabulary at that point. That’s how I learned that I was Jewish. It was quite a shock.

Zibby: You’re so funny. In your book, you have this long list, how to do Jewish right. When you came of age as a Jewish girl in the USSR, you had several concerns you dealt with on a daily basis. “One, does my last name sound Jewish? Two, does it sound more Jewish than this other guy’s in my class? Three, is he Jewish, or he is just unlucky enough to have a Jewish last name without actually being Jewish?” It keeps going on and on. You’re just so funny about all of it. One thing that was not so funny, or whatever, was more poignant, was when you talked about your husband and how he shared with your daughter — I’ll just read this passage. You said, “If you’re surprised that a nine-year-old Jewish girl didn’t know she was Jewish, don’t be. I’m surprised at this myself now, but that’s because I raised my daughter to be proudly Jewish, sent her to a Jewish day school and then to Hebrew school and paid for a large gathering of family members to witness her become a bat mitzvah and then dance the night away on a dance floor filled with thirteen-year-olds. My daughter knew she was Jewish the moment my husband told her about the Holocaust when she was two. He didn’t hold back either. Gas chambers were front and center in that story. I kid you not. For the record, I wasn’t on board. I thought he could’ve waited until she turned three. In contrast, I didn’t know I was Jewish until that boy pointed at me and shared my ethnicity with the whole class because he was proud he could read and that information was readily available in the teacher’s journal.” Telling your daughter at two or at three about the Holocaust, explain that and what the ramifications are of that and how you and your husband decided. I can’t even remember when I told my kids about the Holocaust. I don’t know. I feel like we talk about it a lot. I can’t remember a single moment when I decided to tell them or not tell them.

Margarita: I think I exaggerated it a little bit for humor effect, but she was, I want to say, around maybe four. I don’t know if we decided it or if he just kind of told her. I can’t remember exactly. My grandfather’s, one of the sides of my family, was killed in the Holocaust. He was the only one that actually survived. I still get goosebumps talking about it. For a lot of Americans who grew up here, whose families grew up here, who immigrated maybe in the beginning of the 1900s, the Holocaust was a horrible, horrible thing, but it didn’t, maybe, touch them as close as it touched Russian Jews who lost their families either fighting in the Red Army — my other grandfather was in the Red Army, survived — or having these stories just thrust upon us. My grandfather who lost his family, he didn’t want to know anything about it until ninety-one when he had decided to finally immigrate and join us. He had to get a permission from his family because in those days, you had to get a permission from your family to immigrate. He had to get paperwork from Ukraine signifying that his family was killed. That was the first time he actually learned how they died. For us, for me, the Holocaust is this ever-present piece of my life, piece of my psyche, piece of my body. I think for my daughter, it became this way not necessarily because he told her at four, but because of my family and what we carry in our jeans and in our stories. She’s very active now, obviously, on social media. She’s twenty-one, so that’s where she’s very active on all sorts of anti-Semitism and Holocaust history, etc. She’s still hesitant to go and visit a concentration camp or an extermination camp because she just doesn’t know if she can witness it and be okay after it. I think it’s made an impression on her in that respect.

Zibby: Can you share what your grandfather learned about his family and what happened?

Margarita: Americans think of Holocaust as Auschwitz mostly, Anne Frank. They think of Holocaust as a Western Holocaust, Western Jewry. Eastern Jewry, and that is the Soviet Union Jews, we had different Holocausts. Some people refer to it as Holocaust by bullets because there were no transports. Once the Germans went into the Soviet Union, they didn’t transport anybody to Auschwitz or anywhere. They basically just shot everyone. There’s a huge ravine outside of Kyiv called Babi Yar where I think within two days, I want to say thirty thousand Jews were shot, or maybe more. That’s what they did. They would go into villages. They would say, who’s a Jew? There were quite a few collaborators who would point out their neighbors, people they knew all their lives. They would just take them to outskirts of a village and they would shoot them. Sometimes they would burn them. They would put them all in one house and set the house on fire. Most of the time, they were just shot right there where they grew up after, perhaps for a while, being put in a ghetto and humiliated and tortured or whatever. Yes, my grandfather’s family was all shot in that really small village outside of

Zibby: I’m so sorry. I’m sorry for, early in the morning, you’re delving back into this tragedy.

Margarita: That’s okay.

Zibby: I’ve heard so many stories. It doesn’t ever affect me less. It’s still completely unthinkable. Hard to process the enormity of what happened and how that somehow was acceptable at the time, that it was allowed to continue and be so pervasive and so cruel and awful. It turns my stomach even now. I’m so sorry that your family was involved in that way.

Margarita: Thank you.

Zibby: Thank you for sharing. I think it’s really important to keep the stories circulating, especially as survivors

Margarita: I agree. Just to point out, I’ve been looking at this whole Eastern Holocaust difference and thinking of working on some, perhaps, stories because it is so incredibly different from everything that we know about the Shoah.

Zibby: You should do that.

Margarita: Hopefully, yeah.

Zibby: In your spare time. I’m so glad you wrote this essay collection, though, because you have such a distinct and funny voice on the page which completely comes through. I’m delighted that you wrote this collection, at least first, so I could get to know you better. You, of course, have gone through so much in your own life. You reference this one time. You said, “That was the year I got diagnosed with breast cancer.” Then you put in all caps, “And it was all because of that tree, and also because of the BCRA gene, but who needs science, right?” Because of the Christmas tree which you had just mentioned. You’re very funny. I keep saying funny, but maybe that’s the wrong word. You do have such a sense of humor about all the bad things that befall you in this book, your miscarriages and your breast cancer and all the stuff. Is that how you’ve learned to cope with life? Is that how it sounds in your head? Is it in the writing of it that you find the humor? When does the humor come into the sadness?

Margarita: I think it takes time to digest the sadness and the traumas. Then to put a closure on them is when I use humor. When I started writing this book, it was, in a way, putting closure of some of those moments in my life that were so traumatic. I wanted to laugh at them so that they no longer have, maybe, a hold over me. I think it comes out mainly in writing because somebody’s asked, do you do stand-up? You should do stand-up. I was like, no, definitely not standing in front of an audience and doing that. It does come out mostly in writing for me.

Zibby: Interesting. Also, you mentioned at some point that you wanted to stay alive long enough so that your teen daughter at the time could get all the new models of the iPhone or whatever would be used at the time. Tell me a little more about your relationship with your daughter.

Margarita: We had our tumultuous years, as many people do, when she was between thirteen and sixteen and seventeen. After that, it’s been getting better and better and better. We’re very close. We talk a lot about things. She made a viral TikTok video about how I bought her a vibrator at sixteen or something like this. I think she actually got interviewed on some Canadian radio based on that. I might be misremembering. I decided to do a full swing to the other side from my mother because my mother never talked to me about these things, as those generation mothers didn’t in the Soviet Union. I decided, no, I’m going to talk about everything. There were a few cringy, for her, moments where her mom decided to talk to her about various sexual-related things. We read this book that was amazing, Girls & Sex by Peggy Orenstein, together. Not at the same time together, not sitting together. I would read a chapter. She would read a chapter. I wanted her to have all of that. That’s why I bought her a vibrator at sixteen. We are really close. This is an unfortunate piece of news. You don’t really have to include it. My husband passed away two weeks ago.

Zibby: I’m so sorry.

Margarita: I write in the book that I wrote this book while he was being treated for cancer. He lost that battle. Since then, my daughter and I, we’ve just been so incredibly close. We haven’t been that close ever, even maybe when she was a toddler. It’s really helpful to have her and to just have her as a companion, have her as a friend, have her as a daughter during these times. I’m looking at, as you know, a lot more. I know that she’s going to be there for me. I’m going to be there for her as we adjust to this reality. I’m very lucky. I’m very lucky to have her.

Zibby: I am so sorry. I’m just so sorry. That loss is so fresh and recent. I’m sorry you’re even doing this podcast now.

Margarita: No, not at all. For the first week or so, I just shut everything out. Then you have to resurface. You have to start coming out a little bit. These conversations and things that are outside of it help. Plus, I wrote this book when he was around. There’s a lot about him in this book. My publisher said it’s a testament to him. Absolutely, I’m really happy to speak to you about it now.

Zibby: Gosh. I am just so sorry. I’m glad that this can serve as a distraction and a getting-back-on-your-feet moment. My heart is literally hugging you from afar. I am just so sorry.

Margarita: Thank you.

Zibby: I’m sure you will dip into your humor eventually about these times.

Margarita: I hope so, yeah.

Zibby: Although, it’s not particularly funny. Now I feel silly just being like, and here’s another line I liked in the book.

Margarita: No, please don’t. I would love to because I haven’t touched this book in a few weeks now. I would love to go back to it. Yeah, let’s do it.

Zibby: Another line that I thought was great was when you said, “Every time my college-age daughter fails to call me for longer than a week, I think my mother secretly rejoices.” I thought that was so great because there’s so often this being-caught-in-the-middle feeling between the grandmother and the grandchild and being the mom and in the way and wanting to change the things, like you said with the vibrator, and not repeat the same mistakes. Then you make new mistakes, or at least I do, and how you navigate those two things and how everything you do sort of comes back at you through your child in some way, shape, or form. How has your mother — in this dynamic, how has it been with that dynamic as an overlay to everything else?

Margarita: I can teach a book about being in the middle. Sorry, teach a course about being in the middle. The Soviet immigrant parents, they feel like they need to be involved in every single step of their grandchild’s upbringing. My mother used to call me every day to find out what

Zibby: Oh, my goodness, so funny. I wanted to just quickly go back to your time at Yale. I went to Yale myself, undergrad. I also really did not like going to the Harvard-Yale games. I felt like I was the only one. I didn’t like drinking during the day and standing around at the tailgates. Nobody wanted to even go into the game. That was the part that I actually thought was more exciting, would be to actually watch the football, and nobody even wanted to do that. We just stood around. Everyone looked forward to it. One time, my best friend who actually has since passed away, she felt the same way as me. We snuck off and left town and took a ferry and went far away so we didn’t have to go. Again, you’re not supposed to admit that when you’re one of those players. I was delighted to see that you had similar feelings.

Margarita: For me, Yale was some other-world experience. Here I was, it was ’93, it was barely three years in the country. I’m going to this institution that is so well-known and so revered and so respected. At that point, I may have been the only Soviet there, really, ’93. I don’t necessarily feel myself an American yet. I feel some weird combination of things even though in the book I say I really wanted to be a fully assimilated American. I didn’t understand football. To be perfectly honest, I still don’t understand. I look at it. No matter how many times my husband tried to explain it to me, I can’t understand it. There were certain things that culturally, I just didn’t get. It was a weird experience, a very interesting but weird experience to be a Yalie. Now it’s great because you get all these alumni everywhere that you can get in touch with and say hi. I think it would’ve been different had I come back now and started there. It would’ve been completely different. I think what we go through builds us somehow, so I’m sure it built me in some way that I may not put my finger on now.

Zibby: We were there at the same time because I got there in ’94 and stayed through ’98.

Margarita: Yeah, we were. I was there from ’93 to ’95.

Zibby: There we go.

Margarita: We may have crossed paths somewhere.

Zibby: We may have crossed paths avoiding the Yale Bowl. I think I spent more time at Naples Pizza than anywhere else, Durfee’s for frozen yogurt, and all of that.

Margarita: I think I spent a lot of time in that café on — what is the street? Prospect Street or something? One of those really known coffee houses. What was the name of it? I can’t remember.

Zibby: Atticus?

Margarita: Yeah.

Zibby: I literally

Margarita: I was there a lot too. We bought a subscription to the drama series. I’m from Moscow. I grew up on theater. We went to theater all the time. When I arrived to the States, I was like, where’s the theater? How can I go to the theater? Please show me the theater. Until Yale, I lived in little towns. There was no theater. I bought a subscription every year that I stayed there. It was really great.

Zibby: I’m envisioning the two of us at tables not speaking twenty-five, whatever, years ago, thirty years ago at the little bookstore.

Margarita: I know. Funny.

Zibby: Here we are on Zoom. So what is coming next for you in terms of writing, in terms of anything? What are you thinking? What’s coming next the next few years? I know this is obviously a time of a lot of transition for you now.

Margarita: I don’t know where I’m going to be living, so that’s the first one. I have to figure out where I will live. Then I am in a creative writing program at Oxford University. I’m writing a novel as part of my thesis. That’s coming up for me. My agent has another novel that I’ve written and hopefully will go on submission soon. I spent a long time being part of the foreign service with my husband, and so I’m thinking maybe some collection of essays, what it’s like to be in the foreign service in the diplomatic corp of the United States. There are some really crazy, interesting stories. That’s a possibility. Then I have some Sephardic background. My grandfather was originally from — I mean, five hundred years ago — originally from Spain. I’m fascinated with the Sephardic world, so fascinated. Hopefully, maybe something about that. There’s just so many ideas floating in my head. I probably should stop somewhere and start one of those.

Zibby: Wow. Those all sound great. I feel like I’m always jealous because Sephardic Jews can eat rice on Passover or something. We’re not supposed to do that.

Margarita: Which is why we’ve always been doing this, actually, in my family. We’re like, okay, we get to do that just because you are a part of it but also because we’re vegetarian. It’s really hard to find Passover food for vegetarians.

Zibby: I know. I’m like, well, if the Sephardic Jews can eat it, who knows? Maybe. Even though I’m 99.9 percent Ashkenazi, but that’s okay. Maybe a little rice can’t hurt. Anyway, do you have any advice for aspiring authors?

Margarita: Just keep writing. I started writing really late. I write in a language that’s not native to me. I immigrated to the States when I was twenty, so that’s when I learned my English. If a story is begging to be told, just do it. It doesn’t matter what anyone says. Just do it. Then go back and edit it and edit it and edit it a hundred times because that’s how it gets better. Don’t listen to anyone telling you that you can’t or you won’t or you won’t get published. It took me a long time to get a publisher interested in this collection. Just keep writing. I’m sure that’s the advice that everybody gives, right?

Zibby: Everyone has a unique viewpoint of it. Not everybody writes a really funny, poignant essay collection in a second language, so bravo.

Margarita: Thank you. Thank you very much.

Zibby: Margarita, thank you for coming on. If there’s anything I can do — I know that’s such a trite thing to say, but I’m glad we had this time to talk. I spent time with all of your stories. I feel like I got to know you so well. That’s been, really, a gift for me. Thanks.

Margarita: Thank you. Thank you for giving me this opportunity. I loved speaking to you, a fellow Yalie, and connecting even though it’s online. Hopefully, one day, maybe we will sit at the same table and we’ll know each other.

Zibby: That would be great. Hang in there. Take care. Buh-bye.

Margarita: Bye.