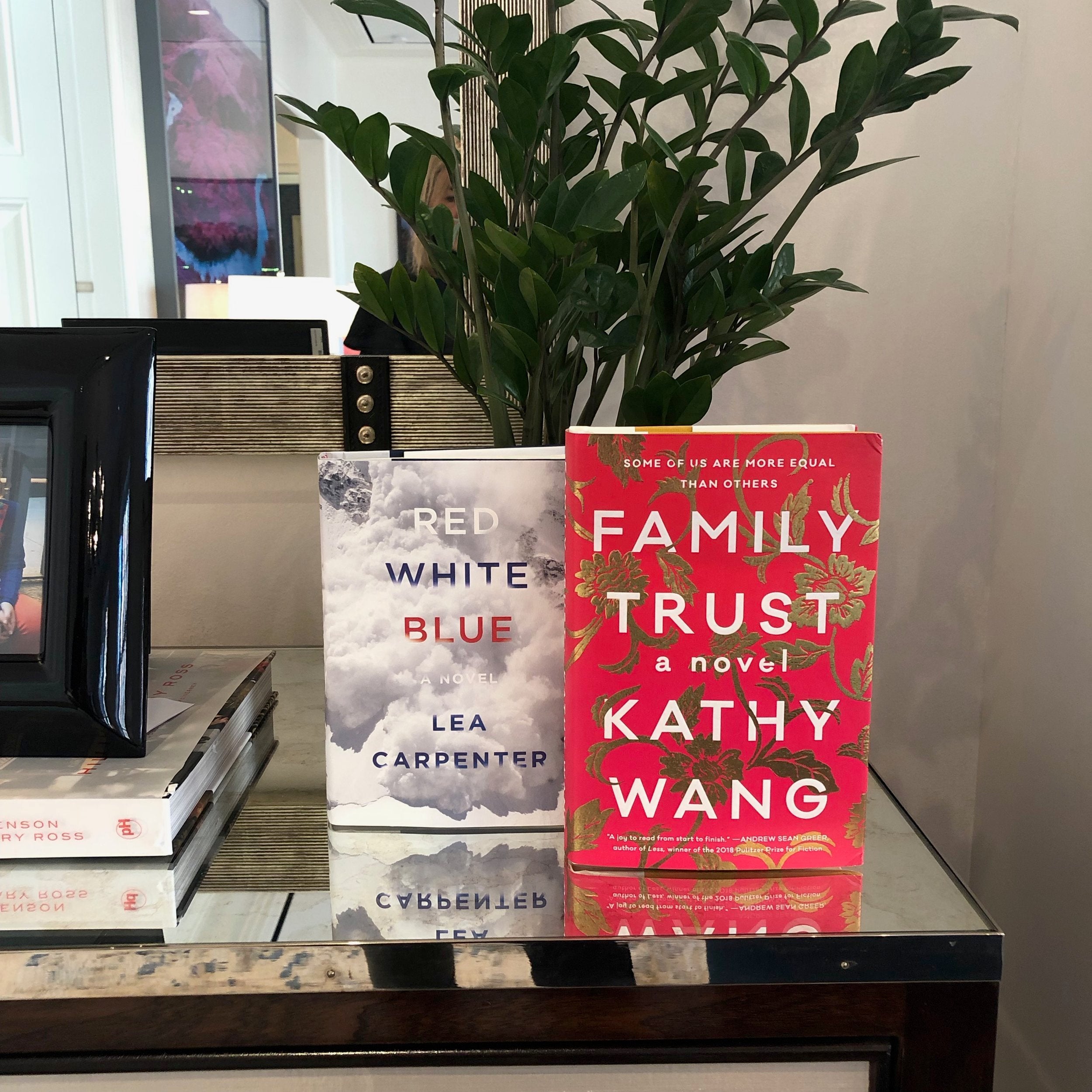

Kathy Wang, Family Trust

I’m excited to be here today with Kathy Wang. Kathy is a graduate of UC Berkeley and Harvard Business School. Kathy spent years working in the tech industry at Intel and Seagate before writing her first novel Family Trust. She currently lives with her husband and two children in the Bay Area where she’s working on her second novel.

Also, just a friendly reminder, please subscribe to “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.” It would great if you could follow me on Instagram @ZibbyOwens and also at @MomsDontHaveTimeToReadBooks. Thank you so much.

Welcome to Kathy. Thanks for comin’ on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.” Kathy, can you tell listeners what Family Trust is about? What made you want to write this novel? What is it about?

Kathy Wang: Family Trust is a multigenerational family saga. It centers on an Asian American family, upper middle class in Silicon Valley. The patriarch gets a terminal illness diagnosis. It follows the various players as they struggle with this diagnosis and what it means. There is adult children in this who have their own lives and their own problems. There’s the first wife who built up his so-called fortune with him. Then there’s his younger second wife who has been with him for some time and is finding caring for an older, dying man a little bit more trouble than she had anticipated. That in a nutshell is the story.

What made me want to write this story — the story actually began with one of the characters whose name is Fred. He is an HBS grad who was struggling with his career in Silicon Valley. For me, when I wrote this at the time, I was definitely at the stage in my career, and so were my peers — I think when you graduate from college, you go along this very established path. You graduated from a good school. You get a good job. Then you go to a good graduate school. You go to a job after that. Then all of a sudden, your career stops for a lot of people. You stop going up. A lot of have been told that we’ll continue to go up. Then you realize that actually for a lot of us, you’re not. Maybe you’re going to plateau there. Maybe you’re even going to start taking a few steps down. That was something that I was going through at the time. What really fascinated me was how the men were handling this phenomenon versus the women. They had very different ways of dealing with this disappointment. It was something that I was obsessed with. From there, I started writing one of the characters. Then it grew.

Zibby: So interesting. You deliberately put your career on hold, not a stalling as you describe it for Fred, but you put your career on hold as a tech manager after your son was born and that’s how you wrote this book. Is that correct?

Kathy: Yeah. My husband had this job at the time where he was probably travelling half the month. We had a baby. I just couldn’t figure out how to make it work in going back to work. I ended up staying home. I definitely felt really weird about it. I was the only person in my entire section who was not working. You definitely have feelings about it.

Zibby: For listeners, Kathy and I both went to the same business school, Harvard Business School. Not many people are novelists/writers. Not many people choose to stay home with their kids. Actually, is that even true? I’m not even sure.

Kathy: It happens later on. Once they have their second, I feel like then a lot of people are like, “This is too…,” mainly women, they step away.

Zibby: The idea of writing a book about what happens when you’re not as successful as you once thought you should be is so interesting. I’ve personally found now that I’m in my forties and people are looking at their careers more analytically, the people who are really struggling with where they’ve ended up are having the most difficult time of it in every realm of their lives. Do you find that too?

Kathy: Do you mean at home and at work?

Zibby: Yeah, especially for people who have been told their whole lives that they’re these achievers and to keep going. They have great educations. They start out with great jobs. Then they don’t fulfil the potential that they believe they can. I feel like it does so much to self-esteem for those people.

Kathy: Totally. I agree with you. When I was at HBS, most people were not married yet, for example. They’re like, “I rock it at school so when I get married, I’m going to be great at that. Then when I have kids, I’m going to be great at that.” Then that actually happens, there’s going to be failures along the way. They have a hard time, like you say, managing that as well.

Zibby: I guess that was my long way of saying people have a hard time managing failure. Although now that we’ve been talking, I’ve been thinking about different, particularly women who I was in school with, who after having kids have started really creative, interesting careers, not necessarily the straightforward jobs that they had right after graduating. Not to say that people aren’t working, all to say, I think that’s a great starting point for a novel, which is probably why it turned into such an amazing novel.

You wrote this book while your son was napping in the afternoons. Is that true? I can’t even get through my emails during nap time.

Kathy: Yes. That was in that one article that came out from my hometown newspaper. It was so funny. The woman who interviewed me, she had a young child. She was really focused on that point. The one thing, I don’t know if it comes across — I did write it when he was napping that year — it was really fueled by a very deep sense of desperation. I needed to have something that was mine, that I was doing on my own, like a little hobby or something. I did do it while he was napping, but at times it was really miserable for me. I would try to do everything when he was awake. “Watch me wash the dishes.” Then he would have a meltdown. It was definitely not that easy.

Zibby: There are lots of hobbies you can take up. Why this one? What was it about writing or writing a novel in particular that really appealed to you?

Kathy: It’s definitely a bucket list item for me. I wanted to try to write a book. I didn’t know what my life would be like after I had two kids. Maybe I’d go back to a full-time corporate career. I was like, “This is maybe the last time I’ll have a big chunk of time for quite a while.” That’s essentially what pushed me to write it. Like any writer too, I’m a big reader. It was something that I was always interested in.

Zibby: Had you written any short fiction or anything, or you just literally dove in?

Kathy: I hadn’t. I hadn’t had any publications. I was like, “Maybe I’ll just go to one of those programs.” Stanford has a program or a fellowship. All of those require letters of recommendation and examples of your writing. I didn’t have any of that. I have almost no choice but to try to write a longer piece.

Zibby: Maybe there’s something to be said for the freedom. Whatever recipe you had for your book ended up with such success. I don’t want to quote your hometown paper again. Can you tell me a little more about the process of selling your book and how that all went down?

Kathy: I had just used for Google for everything. I didn’t have beta readers or anything. I think you know. It’s like when you have a

Zibby: How did you feel when you negotiated your final deal and the ink had dried on the contract? Were you over the moon? Could you believe it?

Kathy: When I signed the contract, I had just given birth. I was not sleeping. It was almost a non-event. I mean, it’s an event. I was probably sleeping three hours a night with the baby yelling. The toddler’s acting out. It was wonderful, but I almost don’t remember it in that haze of that period where you don’t really remember anything from when your kids are little or really young. One thing that I do remember is that was when I told my mom that I had written a book. I didn’t tell her anything until I had received a contract from HarperCollins. I knew if something fell through, I would forever be reminded. “What happened to that book you said you’re going to write?”

Zibby: Oh, my gosh. That’s so funny. Let’s talk about the matriarch of the family in this book Family Trust, Linda Liang, this typical mom except that she and her former husband Stanley have gotten divorced. Stanley’s with another younger woman, and yet she’s obviously still the mom to the two grown children. When Stanley goes through an illness, she plays a very interesting role. You don’t see this a lot, what it’s like for this ex-wife when the former husband/dad is ill. That was a really interesting relationship to examine.

You made me laugh so much when Linda starts dating online with this Tiger Lily app. She goes on a date finally with somebody she had met and says, “In person, Norman looked like his photos, albeit older. When she first saw him, Linda was struck by a grim fear that she too appeared that age and scuttled to the bathroom to reassure herself. She pet her face in the mirror. She didn’t think she looked that bad. She thought she might still even be able to pull off handsome, but there was nothing she could do about it either way. She applied a fresh coat of lipstick.” I just love that paragraph. It’s so well written. You feel yourself in that moment. You’re in the bathroom with her. It’s so perfect about aging and beauty. It encapsulated so much right there. Tell me more about Linda’s character and how you chose to write her.

Kathy: First of all, thank you very much for your kind words. Linda, I hate to say it, I think many Asian Americans will read this and be like, “That’s my mother.” That’s how my mother is. She’s very practical. She’s not very sentimental. She’s very focused. She’s very results-focused. She’s not a hugger. She’s not going to praise you. She wants the best for her kids, but it’s going to come out in a much more direct, blunt fashion than more stereotypically American cheerleading style. That’s essentially her. She was responsible for a lot of the financial success with her first husband. We know they got divorced. Now, she’s seeing that maybe everything that she built up, which obviously he walked away with half with, is going to go not to the adult children that are her children and his children, but actually to his younger, second wife.

Something else that is interesting to me after having published the book, there’s very different viewpoints on that younger, second wife in Chinese culture versus American culture. I’m cliché stereotyping. When an older man marries a younger woman, in Chinese culture, everyone’s kind of like, “Yeah. There’s a deal going on there.” Everyone knows it. She wants a lifestyle. He wants companionship from someone young and pretty. In American culture, it seems to be like it needs to be about true love or it has to be like, “It’s love. Money is not even in the equation.” When she’s dealing with the discussion of his inheritance or his will, to her, it’s just a normal conversation that you have. It’s interesting. I get emails from American readers. They’re like, “What’s wrong with her?” It’s funny because with Asians, it’s not even something that’s a problem.

Zibby: I was definitely surprised reading that. That’s bold. Was your mom similar to Linda in how she raised you or her general affect? Did you base it off of your own family at all?

Kathy: Yeah. My friends growing up, they called her “Asian WASP.” She’s just very a certain way. Everything has to be very proper. She’s definitely similar to Linda in some respects and definitely in her bearing.

Zibby: How ‘bout Fred, the disillusioned business school graduate who’s struggling? When you had his girlfriend Erika stretch the truths about him, it’s almost like what he wishes had happened, the things that she writes, even though he cringes when he reads it on Twitter or whatever. I think he would be happy with the version that she has of him in her head. How did that come about?

Kathy: Fred is actually my favorite character. He’s the one that I think most people dislike the most. My friends from HBS have read it. All the Asian guys are like, “Yeah, this is a normal man.”

Zibby: That’s probably true. Another author, Elyssa Friedland who wrote The Intermission, spoke to my book group the other day. She said that a lot of people had said to her about her characters, “I’m not sure I like them. I’m not sure your character is very likeable.” She’s like, “That’s okay. My goal was not to make my character somebody you want to like. That actually wasn’t at all what I was going for. That’s good.” There’s a lot to be said for you don’t have to like everyone. Just being exposed to some of these characters is fantastic in and of itself. They don’t have to be somebody you want to be best friends with necessarily.

Let’s talk a little bit about Kate, the daughter. Kate is the typical nice girl, or she feels she’s the nice girl to so many others. Then you actually write, “What did it mean to be nice? Nice was a label that been had hoisted on Kate since childhood. ‘You’re great,’ Denny had said way back then, ‘like actually nice, not like so many other Asian women.’” But then soon after you say, “It was the times that she was a bitch, Kate thought now, that she had really excelled.”

I was wondering about this dichotomy between the nice girl and then the bitchy, successful girl. Do you feel that’s a Silicon Valley must-have type of thing? Was it just Kate herself that you found interesting as a character and wanted to portray that way without any sort of more generalized societal commentary?

Kathy: Certainly it’s the case in Asian women. I think a lot of women have this problem in Silicon Valley where you have to be very — in a lot of industries — where you’re supposed to be nice. I think banking is its own separate kind of world where the women have to behave a little differently. In the Valley, you have to be pleasant. People want to have to work with you. Especially when you’re in a business function and so much of your job here is working with engineering talent and working with software, they have to like you for you to get a result. That’s so much of your job.

Being Asian American, there’s a stereotype that you’re very shy. You’re very sweet. You’re soft spoken. Asians, just like any other,

Zibby: I bet some people could argue any group of friends who’s really close can get together and gab and be who they really are. A lot of people have to put on at least some sort of veneer of civility at work. This novel was so great and so rich in so many relationships and aspects and family and everything else. It really had it all, which was fantastic.

Your book deal included two books. I was wondering if you could talk at all about your next book.

Kathy: This next one — I’m sure you’ve heard this from many people — it’s such a struggle. I feel like I used up everything. When I think back on my book, I’m like, “Man, I should’ve not included this part.” I just wasted it there. I

Zibby: When you sold the second book, did you have to agree on what it was about? Can it be about anything?

Kathy: I had no pages. It was literally like I had said something, and they were like, “Okay.” The directive is that it can be about anything within reason. I don’t know what’s going to happen if I deliver a vampire thing or something.

Zibby: Right, of course.

Kathy: Hopefully, they’ll accept whatever I come up with. You see those all the time where the first one comes out and the second one doesn’t come out for ten years. Oh, my gosh. I wonder if that’s going to be me.

Zibby: It’s one thing to write and be creative in the privacy of your own home if you don’t know a hundred percent where it’s going. It’s almost like you’re standing in the middle of Times Square and every word you think of is being broadcast out. That’s a lot of pressure. There has to be some sort of suspension of disbelief where you’re like, “No one’s actually going to read this, so I’m just going do it.” I feel like you’d have to fool yourself into getting the authenticity of the first book. That’s just me. When I know people are about to read something, I get very self-conscious about it, whereas when I’m writing from the heart, it just flows out of me. I don’t know if you’re the same way.

Kathy: Completely. I totally agree. That’s something that’s really interesting to me. I’m not really a user of Twitter. I never used it before I wrote this book. Everyone’s like, “You have to use Twitter,” because everyone in publishing uses it. I’m on Twitter. I normally lurk a lot. I’ll see people tweet. Then the tweet will disappear like they decided not to do it. They delete it because they realize it’s going to be out there. You can’t write a book thinking that way. Maybe that’s really good stuff probably. That was a controversial tweet that they did, that they decided to delete. That’s the stuff that’s really good in a book. If you keep freaking yourself out that someone’s going to hate or take offense to it, a lot of times it’s too difficult to keep going.

Zibby: I actually just finished writing this memoir, which I’ve now decided I can’t sell. It’s a long story. Three quarters of the way through even my husband who read it can tell, he’s like, “This is when you realized that maybe it wasn’t just you who was going to read this.” My agent and everybody, they were like, “What happened here?” I’m like, “I don’t know. I started panicking.” Obviously, my tiny, little story pales in comparison to your major deal with the publisher and everything. All to say I relate to that feeling. I’m sure you will come out of it soon. I’m making assumptions about you here. I’m assuming you’re more like a Type A overachiever that I can relate to in that way. Having something not be perfect is almost unbearable. Creative things sometimes end up not being that way at first. I’m rambling here.

Kathy: I get emails from HBS people who secretly want to write a book. They just can’t get past the second page or whatever. They write it and they have to read it. They’re like, “This sucks.” You want everything to be perfect right away. They don’t understand how truly bad the first draft is going to have to be.

Zibby: No matter how much advice you get from other people — every author I’ve had on here, when I ask for advice to aspiring writers, everyone says, “Just write. You have to start writing. Just do it.” Yet when I try it, I’m like, “I can’t. What should it be about? Wait, the jacket cover.” Our minds get the better of us sometimes.

Do you feel like your life has changed since the book came out? It’s gotten such amazing attention from the media. It’s such a great book. How is it now that it’s out there?

Kathy: It’s the same for me. I live in a suburb in the Bay Area. I’m not in a big writing community. It’s the same for me. I’m trapped in my house with my kids. I didn’t do a book tour, for example. For listeners out there, these days, unless you’re a really major author, I don’t think publishers really fund book tours anymore. I didn’t do one. I’m just doing a few events. Otherwise, everything’s basically the same for me. There’s not that much that has changed. Even the most famous author in the world, which I certainly am not, is still below a Z-list celebrity. There’s nothing that’s really too different.

Zibby: I know. That’s the thing I can’t understand. You can walk into a room full of the most brilliant, accomplished authors, and no one will even know who they are. It’s insane. It’s crazy. There should be so much more attention. That’s part of why I do this podcast is to give writers a platform. Great books like yours might fall from the radar if the people don’t hear about it. Getting the word out is so important.

Kathy: You know what’s interesting? I hate to keep going back to the fact that we both went to business school. When I learn about how much even very famous authors sometimes get paid, that’s like a mid-level whatever at a bank or something.

Zibby: There was a recent article that said the medium salary for writers is $21,000 a year.

Kathy: I saw that too.

Zibby: Come on. This is fair? Is this how we value the contribution? If I curl up with a good book and it amuses me for twelve hours and makes me think and transports me to this other world, I would pay so much more than I would even for a movie for that. Think about it. Life is not always fair.

Kathy: I saw that. That was incredible, in a bad way.

Zibby: I know. I can’t believe it. I also remember in some operations class at business school that I took, there was somebody who was a writer or in some way doing some sort of writing something. I remember them saying that they viewed themselves as just a producer of any other product, but their product was words. They approached it like they were just going to market it as if it was the latest iPhone or a new pair of shoes or whatever else. The end product was no different in a way. That’s basically all I learned about writing from business school. I don’t know about you.

Now that I’ve talked a lot about other advice I’ve gotten from writers, what advice would you have to somebody just starting out? Yours is such an inspiring story. It can be done. You can just take a go and have it really pay off. What would you tell other people who are attempting it?

Kathy: Backpedaling a little bit, I keep this journal. It’s a five-year journal. Every day you can look back and see how you felt a year ago on the same day, and two years ago. It’s funny because I after I finished the book, you forget a lot about how much work it is. When I go back and read the entries from when I was writing it, I felt like a failure a lot of the time. I felt like the book was failing, that I was failing, that things weren’t working out, that there are these huge plot holes that I was not going to be able to figure out. My advice would be that when you’re writing your book, you’re going to feel that level of failure, and that the project can’t be completed, and that there’s no way that this is going to be publishable. My advice would be you have to understand that is a feeling that you have to have in order to move forward into a publishable product, from my perspective. It’s entirely normal. It’s necessary. If you feel that way, know that it’s a feeling that a lot of writers have. A lot of writers have that feeling with every single book that they write. It’s normal. Don’t feel that is necessarily a pronouncement on the ultimate publishability of your work. It’s part of the process.

Zibby: Or maybe your book is terrible.

Kathy: There is always a possibility.

Zibby: We’re assuming that everybody out there is writing really great books, so that’s not going to be the case.

Kathy: What are you reading right now?

Zibby: What am I reading right now? I just finished reading An Anonymous Girl by Greer Hendricks and Sarah Pekkanen.

Kathy: How was that?

Zibby: It was good. I’m interviewing them tomorrow. It’s good. It’s a page-turner.

Kathy: I read their earlier one.

Zibby: I don’t usually read thrillers, but it was good. I was like, “Why don’t I usually read thrillers?”

Kathy: I like thrillers. I think there’s a huge market when they’re well written. You have to have the minimum level of readability. They did a great job with The Wife Between Us. I just finished A Terrible Country by Keith Geseen.

Zibby: How was it?

Kathy: It was good. I had an interest in Russia. I had gone there for about a month. It was interesting to me. I didn’t know anything about Keith Geseen before I read it. Then I googled him. He’s this

Thank you so much for having me on. It’s amazing that you do this series.

Zibby: Thanks. Thanks for comin’ on.

Kathy: Please, I think you should try your memoir, by the way.

Zibby: I think I’m going to rewrite it as a novel. Then it feels like maybe I’ll have a little more freedom.

Kathy: That’s always a good way.

Zibby: I just don’t really know how to write fiction, but it didn’t stop you. You did a great job.

Kathy: I think you know more than you think given everything that you read, how much you read.

Zibby: You’d hope.

Kathy: Thank you, Zibby. Have a good day. Bye.

Zibby: Thanks, you too. Buh-bye.