Dr. Inger Burnett-Zeigler, NOBODY KNOWS THE TROUBLE I'VE SEEN

Clinical psychologist Dr. Inger Burnett-Zeigler joins Zibby to discuss her new book, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, which grew from her 2018 New York Times article, “The Strong and Stressed Black Woman.” Inger and Zibby talk about the different ways in which Black women are sharing their experiences through both fiction and non-fiction, the effects of intergenerational trauma, and how Inger’s grandmother not only inspired her to write this book but to also claim all of the goodness the world has to offer.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Inger. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books” to discuss Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen: The Emotional Lives of Black Women.

Inger Burnett-Zeigler: Thank you so much for having me.

Zibby: It’s my pleasure. Can you tell listeners a little bit about what the book is about? What inspired you to write it? When did you decide you wanted to do this, the process behind it, all of that? Then I want to talk about your own family if you don’t mind.

Inger: Sure. The book really grew out of an article that I wrote in 2018 for The New York Times called “The Strong and Stressed Black Woman.” In that article, I talk about a woman that I was working with in therapy and I talk about my grandmother and the many strengths that they had, achievements that they had accomplished in their lifetimes both being professionals and raising families and also simultaneously dealing with trauma that had not been addressed and that trauma having a really significant impact on not only their physical health, but also their mental health. That was really the seed of the book. This book, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, is an integration of personal story, stories of friends and family as well as clients that I’ve worked with in therapy and really showing how they present themselves to the outside world, that strength, that resilience, that grit, tenacity that allows them to push through and overcome everyday challenges, but also all of those other things that lie beneath the surface, the stress, the trauma, pregnancy trauma, childhood trauma, relationship trauma. Along with those stories, there is an integration of research about various mental health conditions as well as clinical coping strategies for how to deal with stress and trauma and live a healthier life.

Zibby: Which, by the way, everyone in the universe could use right about now, I feel like.

Inger: That’s right.

Zibby: Really great tips. This is the most stressful environment. Widely applicable advice and actionable steps, which is always fantastic. It’s so funny, I don’t know if you come across this book by Jayne Allen, that’s her pen name, called Black Girls Must Die Exhausted.

Inger: I’m familiar with it, yes.

Zibby: Her real name’s Jaunique. We recently did a podcast, after which I was like, “You have to join my team for Zibby Books.” Now we work together. We just did a Q&A for book club. It’s funny because, exactly what you’re saying, she decided to do in fiction. She had the same desire, the same goal. There was all this stress. Everybody was so tired. It was just so much to hold onto. She decided to approach it with fiction. You’ve decided to go at it more with studies and with your experience. Yet you’re coming at two sides of the same coin. As a reader, they’re just different ways. You can immerse yourself in a fictitious person’s lived experience. We can hear about your experience. You can report on it. It’s a nice compliment to get this 360 feeling of what it’s like. We all have different experiences in life. I want to know, I want to hear what it’s like for everybody and for you and what it’s specifically like for black women. This is like a handbook. You’re like, I get you. I hear you. This is all about us. This is what I want to tell you. Read it. Learn from it. Here you go. In parts, I felt like, I’m sorry, I’m just going to read it too. Obviously, I’m not black. I’m sorry, I’m not your target audience, but I found it so interesting and informative. We’re all women. There’s still so many commonalities. Yet the differences are so important to learn about and hear about. Anyway, I’m rambling. I’m sorry. Let me let you talk. Go ahead.

Inger: I appreciate you saying that. Indeed, the target audience was for black women, but I do think it’s widely applicable to women, to anyone who has experienced stress, depression, anxiety, for mental health professionals, for those who are supporting women or others that are struggling day to day. I really appreciate you saying that. I couldn’t agree more in terms of the ways that fiction is approaching this same topic. When I was writing, I deeply immersed myself in other fiction that was addressing some of the same issues around black women. Queenie is a book that’s coming to the top of my mind. I love the way that fiction can tell stories. Although these are not real stories, they’re still about real experiences. That’s something that I really wanted to channel in the book as well because I think that that’s what really helps people to relate and to feel seen, as you said.

Zibby: While you’re both out promoting your books, you should do an event or something together. That’s my two cents there.

Inger: That would be great. I’ve been following the success of her book and really appreciate the work that she’s doing as well.

Zibby: I’ll put you in touch afterwards. Back to your book now, there is one section — you wrote a lot about your family, your mom, your grandmother, all of it, even beyond that, how everybody sort of came to be. You wrote about it in a beautiful way too. I just really loved this one passage. I’ll read the paragraph before it too, which is more statistics. This is an example of how you meld statistics and research with, honestly, more like literary writing at the same time. You said, “Eventually, when she was more than fifty years old, Grandma moved out of public housing and returned to school through a program offered by her employer to earn her bachelor’s degree at Roosevelt University. At the time, only eight percent of black women in the United States had a college education.” By the way, I could not believe that number. “In the early 1970s when predatory lending, redlining, and restrictive covenants were rampant in Chicago, she purchased a ranch house facing the train tracks of the previously Dutch community of Roseland. White flight was at its peak as black folks rapidly began to occupy the neighborhood. With every visit I made to Grandma’s house, she planted the seeds of my self-worth and willed to me her expectations for greatness. They were steeped in the Lipton’s lemon tea that we sweetened with packs of Equal and sipped out of pink porcelain teacups. We drank and held our pinkies out while speaking in fake British accents. She and I sat in perfect manner in her ornate wooden dining room chairs which swallowed my petite frame and left my feet dangling beneath the table as we delicately placed the teacups down on the saucers. We pursed our lips together and fluttered out eyelids mimicking the air that we imagined rich and important people had. ‘Be still and stop kicking,’ Grandma said, teaching me how to be proper and dignified.

Inger: That’s one of my favorite passages. I’m so glad you picked that one.

Zibby: Really? I loved it.

Inger: Really fond memories of my grandmother, as that passage shows, of her teaching me how to show up in the world as a little black girl and as a black woman, how I should present, how I should behave, acting with dignity and respect, and more importantly, knowing that I was deserving of all of the goodness that the world had to give me, that I should claim that as my birthright.

Zibby: It’s so amazing that she instilled that in you. That’s really special.

Inger: She’s a very proud woman. In the book, I talk about her being, really, my first example of a strong black woman. She carried herself with a lot of pride. She was very strong in her spiritual foundation, believed in doing things properly. She was able to accomplishment a lot in life, going back to school and having a great career and owning a home. I talk in the book about this big blue Cadillac that she drove, which was really her pride and joy. As I also mention, there was also so much about her life that I didn’t know about until I was much older and even more that I learned about through the process of writing this book.

Zibby: It’s so interesting. She seems like she was a pretty awesome lady. I hope that she’s hanging out with my grandmother up there. I think they would get along. My grandma was a piece of work. You also identify — not you. You draw attention to what Joy DeGruy wrote about in her 2005 book, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome. You said that “Black people experience this syndrome as adaptive survival behaviors due to generations of oppression of enslaved people and their descendants. She suggests that patterns of behavior reflective of post traumatic slave syndrome include poor self-esteem, feelings of hopelessness, depression, suspiciousness of negative motivation of others, propensity for anger and violence, and internalized racism. These maladaptive thoughts and behaviors originated as survival strategies in the context of slavery, followed by systemic and structural racism and oppression, and have continued to be passed through generations long after they have lost their contextual value.” Then you talk about epigenetics and all of that. Tell me about this syndrome. This is not in the newspaper every day. Let’s just say that. People don’t use that term. Inherited trauma, yes, but it obviously applies to a lot of situations that people have experienced trauma in. Tell me a little bit more about that and the way you see that affecting things.

Inger: She gives this title of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome, but I think we really can understand it more broadly as a trauma response, not only an individual trauma, but an intergenerational trauma response that shows up in how we see ourselves, our self-esteem, our self-worth. It shows up in our mood and emotions, that sense of fear, that sense of being on edge, that sense of suspiciousness that something bad is going to happen that’s rooted in either a direct experience with trauma or a close experience with trauma through friends or families or neighborhood environment. It also shows up — you mentioned the next paragraph in which I talk about epigenetics being passed down through the genes. Those who have experienced a trauma, it’s suspected that that can leave an imprint on the genes that’s then passed down to future generations and impacts their physical and mental health even if they have not had their own direct exposure with a traumatic event. I really wanted to highlight that because I think so many people that have experienced trauma — I referenced that an estimated eight out of ten black women have experienced a trauma. A fraction of that go on to have traumatic stress symptoms or PTSD. It’s unrecognized. When it’s unrecognized or unidentified, then we’re more vulnerable to passing on these behaviors, passing on these thoughts about ourselves even in our language with how we talk about ourselves and talk to our children and talk to our family members. It’s really the acknowledgment and recognition of the experience that then empowers us to be able to break that cycle and alter behavior, get the support that we need in a very intentional way.

Zibby: On my podcast, it just came out yesterday — although, I interviewed him a while ago — there’s a man named Jesse Thistle who is an indigenous person of Canada. He was talking exactly about what you’re saying in that you have to have your trauma witnessed. Before you can get past it, it has to be acknowledged and then dealt with. If it’s just out there and nobody is addressing it, then you can’t get past it. You’re saying it’s all — not just you. It ripples. If you don’t get it addressed now, then you’re passing it down. There’s even more urgency to getting people to pay attention and be like, oh, I see. You’re actually really affecting the mental health of all of your — there’s quite a loaded responsibility there.

Inger: You know, avoidance is a trauma response. That is a clinical symptom in and of itself. It’s understandable that we would want to avoid thoughts and reminders of difficult, painful experiences, whether that be broadly the experience of slavery, whether it be some more close experience of abuse or domestic violence or what have you. It’s that turning toward or, as us clinicians say, approaching the trauma, holding space for it, acknowledging it, developing the tolerance to be able to talk about that pain rather than pushing it down and dismissing and avoiding it that really creates the landscape for healing and to be able to move past it.

Zibby: As I said before, a lot of people, I feel like, have a lot of healing to do right now in particular. This is a really good reminder that the things that fester, my old therapist used to say they’ll eventually come out sideways. They will come out in some way. You might as well just deal with them.

Inger: We’re talking about the challenge of right now, the pandemic and everything else that’s been going on in the world. The stillness that the pandemic forced upon a lot of people has been really uncomfortable for a lot of folks that deal with their trauma by being busy, by being distracted, by being out and doing things all of the time. The world is opening up a little bit now. In that period of time when people were really forced to be with themselves and not have as many other things going on as they may have typically had, that was difficult for a lot of folks. That gives room for the thoughts that perhaps we were not paying attention to at another time.

Zibby: If only they started a podcast every single day and had like fifty-seven new businesses and whatever.

Inger: It’s true. Staying busy is definitely one that I think a lot of people and women, for sure, can relate to.

Zibby: I like how you posed a lot of questions to the reader instead of just being prescriptive. That’s a hallmark of a good therapist. You’re asking open-ended questions and all of that. “How did I receive love from my caregivers? What were my early models for intimate relationship? What wounds do I still carry from childhood or past relationships?” Then you talk about the trauma bond and how all of that comes down for generations and everything. If you want to not avoid, you’re inviting people to get into it here, I feel like.

Inger: All of this is an invitation. I think that that’s an important kind of concept to hold in reading the book or if one is to go into therapy. Often, there’s this idea of, what are they going to make me do or think about? This kind of pressure. As a therapist, it’s important to go at the pace that the person that you’re working with allows. I actually had a close friend talk to me about that passage. She was reading the book. Really successful, highly ambitious black woman that has struggled in relationships. She was saying that she read that passage and she was asking herself those questions. It got uncomfortable. She keeps coming back to it. All of this is like planting seeds. You might notice the discomfort, move away, and then you can come back as you’re ready.

Zibby: What is your life like when you’re not helping a zillion other people in your practice and by writing books and lifting people up and all of that? What do you do when you’re not working? What’s your story? What do we not know from the book?

Inger: In terms of work, I’m a practicing psychologist. Most of my effort is in research focused on mental health in the black community. I’m also deeply involved in mental health advocacy at the city and state levels. Do a lot of volunteer work with various mental health and health care organizations. Aside from all the mental health stuff and work stuff, I really love theater. I love the arts. I love yoga. I love health and wellness. I love restaurants and museums and hanging out with my friends. I love rest. I preach rest clinically. I like non-doing. I think that there’s a lot of benefit of just being still without having a goal, if you will, attached to it. That can be rejuvenating and fulfilling when we lead otherwise quite busy lives. That’s something that I definitely like to practice for myself as much as I can.

Zibby: I like that. I like that because you’ve given it a purpose. Now you’ve given rest something you can accomplish.

Inger: Check that off. I rested today.

Zibby: Every two weeks, I’m like, I should probably take a little bit of time to rest. This is good for me. Okay, good, I did it.

Inger: As a kid, I really liked journaling. As I moved into my professional career, I had lots of thoughts and opinions about many things. My dad always said, “You should write about that. You should write about that.” He really planted this seed in terms of meaningfulness that can be gained from writing. I would say in the couple years before I started working on the book, I became really intentional about writing op-eds, particularly as an academic. I thought it was really important to be able to share the knowledge that is cultivated in the academic space that often doesn’t get out into the general population. I write a lot about trauma. I write a lot about the impact of the violence in Chicago, about black women’s mental health, about social or political issues and how it’s related to mental health. Now I’m still writing. I just write thoughts. I have my little notebook here where ideas pop up for me.

Zibby: Let’s see. Hold it up. Ooh, I love it. My teenage daughter would snatch that right out of your hands. That’s a good one.

Inger: I like to have a place where thoughts come to me. I can write them and then make something more meaningful out of them later. I noticed that that’s the best process for me. In terms of a next book, right now, I’m trying to be in this moment and hold space for this book. I’m really enjoying these kinds of conversations, hearing about how the book has impacted people. I do have a little seed. That seed is around black women’s joy and the role of black women’s joy in our survival, in our existence in the world. I definitely think it’s important to give some space and attention to that as well.

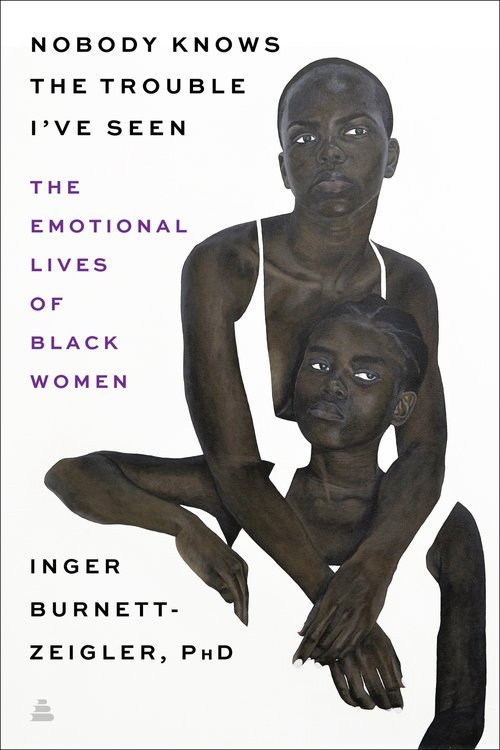

Zibby: Tell me about this cover.

Inger: This is an artist in Africa. Her name is

Zibby: It’s okay. We’ll do a little Rorschach test for you here.

Inger:

Zibby: I love it too.

Inger: She’s another person I would really love to be in conversation with if the opportunity ever allowed. I think there’s a lot of synergy in our work.

Zibby: Interesting. Maybe for your next book. They can be jumping up and down. Maybe they’ll be smiling.

Inger: Oh, wow, that’s the first time I’ve been asked that question. I will share the advice that I read and really took to heart, which is that writing is a practice that you have to do consistently. I think that there’s this myth that you wait to write until the idea comes to you or the inspiration comes to you, but I really found a lot of benefit from the continuously doing and actively engaging that muscle and then worrying about the editing and making everything beautiful later. Just write, write, write.

Zibby: Are you reading anything good lately? Then I’ll leave you alone. Just wondering.

Inger: Right now, I’m reading Ashley Ford’s Somebody’s Daughter.

Zibby: I had her on this podcast.

Inger: I’m really loving that. A lot of good stuff out there right now.

Zibby: Yeah, there is a lot of great stuff out there. Amazing. It was so nice to get to know you. I’ll put you in touch with Jaunique. Thank you so much. Thanks for letting me be the interloper in this book that wasn’t intended for me.

Inger: I appreciate it so much. Thank you for having me.

Zibby: Take care. Buh-bye.

Inger: Take care.