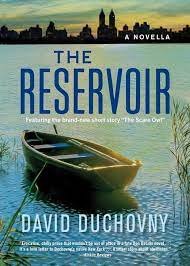

David Duchovny, THE RESERVOIR: A Novella

Golden Globe-winning actor and New York Times bestselling author David Duchovny joins Zibby to discuss THE RESERVOIR, a fever dream of a novella about a lonely ex-financier who is stuck in his apartment during the pandemic and becomes obsessed with the Central Park reservoir, slowly going mad. David shares this story’s inspiration and delves into the themes of loneliness, resilience, the allure of conspiracies, and the psychological impact of isolation. He also talks about his new podcast “Fail Better” and shares his thoughts and advice on writing, acting, and the creative process.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, David. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books” to discuss The Reservoir: A Novella.

David Duchovny: I had the moms in mind because I know they don’t have time to read books, but maybe they have time to read a novella.

Zibby: Totally. I was like, oh, this, I can do for sure. If I can’t get through a novella — one time, I was on a plane, and I wrote this whole long thing. I was like, is this a book? How do I know if it’s a novella? I was searching, how many words is a novella versus a book?

David: It’s not a rule by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s a thing. I did the same thing because I was like, is this a short story? I know it’s not a novel. Is it a long short story? Novella is such a nice, old-fashioned kind of term. I like a novella. It’s like a popsicle, a diminutive of something. I like it.

Zibby: I think novellas need to make a comeback, actually, because you’re right, you can read them faster.

David: You can put it in your back pocket like your J.D. Salinger short stories.

Zibby: You feel more literary just even holding it.

David: Just put it on your table.

Zibby: We were just talking about the reservoir itself. I, being from New York, have grown up going to the reservoir, which plays a central role in the story. I remember my lacrosse team in middle school, we had to cradle the ball running around the entire reservoir. I’ve been there many, many a time, as all New Yorkers pretty much have because it’s such a pretty place. It takes a very dark role in your story. Talk a little bit about what The Reservoir is about and when and why and how you were inspired to write it.

David: I grew up on 11th and 2nd Avenue, so I was not really a park guy. I did go to school, as I mentioned to you, at Collegiate, which was on the Upper West Side. I played baseball in the park. I got to know the park a little bit in high school, even though I was really just hanging out with my new friends from high school who lived up there. It was really when I raised my kids when we moved to New York — I lived on Central Park West there. I had that view of the reservoir. I really got to know the park a little better. It featured somewhat in a novel I wrote called Miss Subways. It was always feeding my imagination from that point on because it was this weird thing. Having grown up, as I said, downtown, it just wasn’t really part of my life. Then to realize you have this huge thing in the middle of this asphalt jungle — it’s hard to imagine the city without it. Yet it’s not really a place for people who are outside the city. Maybe it’s a nice place to take a walk or whatever, but it’s not really what people come to New York for. I think it’s really what people who live in Manhattan rely on in many ways. It’s like a safety valve just to release pressure, in a way. I really began to get into it that way. I had this great view of the reservoir and of 5th Avenue across the way. During the pandemic, there was really nothing much to do but look out that window.

The story just came to me in bits, like, oh, Rear Window. What if somebody was in one of those windows on 5th Avenue across the way? Then the nature of the pandemic reminding me of Death in Venice and all the discussion and the awareness of the proximity to actual people. Six feet was this magical distance. It was very new, obviously, to all of us, but not historically. There have been plagues or whatever. A lot of literature has come out of plagues. Canterbury Tales, in the backdrop of that is a plague. They’re going on a pilgrimage during a plague. Castle of Crossed Destinies by Italo Calvino is set in a castle during a lockdown of sorts. Obviously, Death in Venice, Aschenbach, the protagonist of that, doesn’t really heed the lockdown. He’s pursuing his obsession of Tadzio, the young Polish kid in Venice, and not paying heed to the fact that he shouldn’t be eating those strawberries or hanging out at all. He should go back home. That all just coalesced into some kind of modern-day story of a lockdown. It seems like whenever we go through things these days, in terms of media, everything seems like, oh, it’s the first time this has ever happened. We kind of tell ourselves we’re in uncharted territory when I’m not sure that that’s true most of the time. It wasn’t true this time. I thought there’s some old wisdom there. There’s stories to be told through these kinds of times that relate down the ages and relate to ourselves. That’s just what I thought I was doing when I started it.

Zibby: Interesting. It doesn’t have the same feel, though, as a typical, “this is about lockdown,” because it’s so much the interior life. This is about your grasp on reality and what happens when it starts slipping and the city of New York and so much more with 9/11 and just other things that have brought the city to its knees and how we keep recovering.

David: Also, what’s different about lockdown in our age is that we have — the old literature has people in lockdown telling each other stories. The way into the work is, okay, we’re all sitting around a campfire. We can’t go anywhere. We’ve already exposed ourselves to one another. We’re either going to die or we’re not, so let’s tell each other stories. The difference between this lockdown was that we had our screens. We had connection to the outside world in an unprecedented, intense way where we had more information in thirty seconds than people would’ve gotten in a lifetime in some other age. That’s the different reality we do live in. Obviously, that had spawned and that continues to spawn conspiratorial thinking. Basically, conspiracies, to me, are just stories that people were telling. It’s very similar. People started telling stories during the lockdown by talking about conspiracies, trying to make fictionalized sense of what they saw going on around them. I thought, this is interesting, to go inside the lockdown. We’re all kind of locked down in our own minds anyway, right? That’s the way we live. We’re isolated in some way. What do you allow in? Aside from being six feet away, can’t allow the physical in, but what’s your screen for the screen? This guy, as he gets lonelier, psychologically sicker, he also gets physically sicker. Symptom or symbol? is a question in the book. There’s all these, what is an actual sickness? What is a mental sickness? All these kinds of questions that arise.

Zibby: Of course, the pandemic sort of makes all of us go out of our minds a little bit. I can’t even imagine without the phones. Although, I feel like there was quite a negative perception of the phone in the story and how it ends up.

David: Absolutely. I’m an old fuddy-duddy that way. I’m from a different generation, so it’s not native to me. The way my kids treat it is different from the way I treat it. Sure, it’s convenient and everything, but I can’t imagine a way in which it’s made my life better. If I got into trouble somewhere and I needed to make a call, that would be great, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Zibby: In the story, of course, when he is in trouble, he’s like, I know my kids taught me. What am I supposed to press? Two buttons? What am I supposed to do?

David: The phone does come in handy because he throws it at the guy, and he hits him.

Zibby: Yes, of course. I know.

David: I think the way a phone can really come in handy is if you use it as a defensive weapon.

Zibby: A weapon, yeah.

David: Only defensive, though.

Zibby: Okay, defensive weapon. I don’t even know why I carry mace. That’s a total waste.

David: Don’t need that

Zibby: Exactly. Can I read a passage that I thought was so awesome?

David: Sure.

Zibby: This is about New York. You say, “Thousands of windows lighting up now like rectangular hearts beating, contagious to one another, multiplying exponentially until it seemed the entire ghostly, locked-down city and all its cordoned-off lonely people had begun communicating again crying, ‘I see you. I see you. I see you,’ reaching out to one another across the dark moat of a park. It struck him as beautiful to behold, the city confusing itself for a Christmas tree, seeking connection through the speed of light, tired of this smothering killjoy pandemic and its careful, puritanical distances. Ridley elementary backstroked cheerfully as an otter, and glancing down south, he watched in awe as the Empire State Building winked at the Chrysler Building, and the Chrysler winked and flirted shamelessly back, that mile-high, glamorous silver art deco couple, like estranged royalty reuniting before his eyes. The city was falling in love with itself again, coming back to life, and he felt honored to bear witness.” That’s gorgeous. That is a gorgeous passage.

David: Thanks. When I was listening to it, I was like, that’s a lot of adjectives, buddy.

Zibby: Really? Oh, my gosh. I thought you would be thinking, wow, did I write that? That was so beautiful.

David: It gave me goosebumps, kind of, just because I like not necessarily the writing, but I like the idea. It reminds me of that moment or those days or that month or that year when the city just started to come out of the pandemic. New Yorkers, we complain about everything about New York. We claim to love it, but we just complain about it. At that point, it was just love. It was like, yeah, the streets are fucking filthy and crowded, and it’s all right. There’s that moment when you’ve lost everything and you realize, hey, things were pretty good. Things were pretty good then. It’s like falling in love again, which is what it says in the passage.

Zibby: Beautiful. As I mentioned before, you talked about 9/11 and how everything that was important to us became so clear. It was so front of mind. Oh, this is what’s important. Then a year or two later, you’re like, well, I’ve kind of lost hold of that. Everything’s just back to the way it was.

David: Just human nature, I guess. Intense times tend to make you focus on survival and what’s important, so you cut back on the luxurious things. You cut back on the extraneous things. You realize, oh, yeah, all I need is a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, whatever. That’s great. If we could hold onto that, that’d be fine. All of a sudden, we’re like, I don’t really like peanut butter.

Zibby: I feel like this is a good conversation because I’ve been complaining so much lately about the city and how it doesn’t feel safe lately. Everything’s going out of business. There’s garbage everywhere. I’m always like, should I move? I’m never going to move. Why do I even talk about this?

David: I moved. I grew up — well, you grew up there too. For me, it was enough already. I’ll always enjoy going back, but I like a clean slate after a point too.

Zibby: I’m thinking maybe when my kids are in college.

David: That’s what it was. I didn’t leave until my kids were gone.

Zibby: I’ve got quite a bit to go, but that’s okay. Counting down.

David: Day by day. Bit by bit.

Zibby: Another funny thing that you did in the book is even though your main character is curmudgeonly in a way, he also sort of defies the typical grandfather stereotype where you think, oh, the grandparents will be so happy when I call. Here, he’s like, the grandkids are so annoying, and the last thing I want is for them to get on FaceTime and pretend that they want to talk to me. I love that.

David: I don’t have any grandkids, but I imagine they won’t want to talk to me

Zibby: That’s so funny.

David: My kids barely talk to me, so I can’t imagine my grandkids wanting to talk to me.

Zibby: That’s another interesting part, is his relationship to his daughter as she worries. Obviously, he’s descending into his own mental stuff, but wanting to figure out how to preserve that relationship. Then there are observations you have just about life, like when you have him sitting on the ground and thinking, how did people dig graves when the ground was this hard and there were no machines? I’m like, yeah, right? How did they do that?

David: They were just tougher than us.

Zibby: I guess so.

David: If you’ve ever tried to touch the ground in Central Park in the middle of winter, that’ll just pull your nail right off. It was a scene where he’s trying to find something to throw at that guy before he throws the iPhone at him, trying to find a rock or a pebble. It’s just hard, slaty soil.

Zibby: I’m embarrassed to admit I did not know that Central Park was once used as the burial ground for enslaved people.

David: I’m not sure that I knew that. Maybe I knew that.

Zibby: Did you make that up, or is that true?

David: I’m pretty sure I didn’t make it up. I know it was a potter’s field at some point, which is for unclaimed bodies or unknown deceased. I’m sure I researched that, but I didn’t know it. I think I was just researching general facts about Central Park. I was researching the reservoir, when it was really last used. What’s the deal with it? All that stuff. The history of New York is very interesting. Any kind of history is, but a big city like that, there’s a lot of — the story is kind of getting that too. If you think of the city as a person, it has this kind of repressed history, unconscious whatever, things it would rather not think about that it did in the past, things like that. If it’s a father, mistakes I made, things like that. The city has a return of the repressed or an unconscious. When the city is sick, like during the pandemic, then the city also is having hallucinations. He’s like the conduit for a city hallucinating, in a way. I’m just making that up right now, but it sounds good.

Zibby: Let’s go with it. I like it.

David: That’s what I meant to do. That’s what I meant to do.

Zibby: What do you want the reader to take away from your story?

David: It’s a good question, but it’s not something I’ve ever asked myself. When I’m writing something, I’m trying to service the thing itself. What does this thing want to be? I’m not really thinking of the reader. I really wanted to have a sympathy for the conspiratorial mind. I think it’s all bullshit, all the Trumpian kind of stuff out there, but I wanted to investigate how it’s comforting and how it’s attractive, how it can seduce, in this case, a sick guy who’s nearing the end, on some level knows that and wants the answer, the part of us that wants the answer. The answer is not Jewish space lasers. I wanted to write a story in which I had an intelligent man fall prey to the need for it to make sense because the truth is there really isn’t one bad guy. There’s not even a cabal of ten bad guys. It’s just groups of people trying to do their best, usually, and some genuinely bad people doing things, but they’re not organized. There’s no organized conspiracy. That’s just movies and TV. We want that. We clearly want that because we want to blame a bad guy. We want to have a hero. We want to have a good guy. That’s what I wanted to do, was show how when you get lonely, you’re susceptible to wanting the kind of comfort of the big-A answer, the big-T truths, or whatever. I got it. Now I can move on.

Zibby: Interesting.

David: I just answered that to your question — I read this interview with Joyce Carol Oates where she was saying very intelligently, I just answered your question. I never thought of that. I don’t even know that I believe what I just said. You know what I mean? Because you’re just kind of trying it out.

Zibby: So what do you think? How did it sound?

David: It sounded okay. It sounded good, but next week, I might go, no, that wasn’t it.

Zibby: Just let me know. I’ll delete it.

David: I’m going to do an acting job in Europe today, actually, which is why I was late. I’m just forgetful. I just started a podcast yesterday. I’m going to do a ten-episode podcast with Lemonada, the podcast company. I just did my first one yesterday. I was in your position. It’s different. I’d never been the interviewer. It’s a learning process. It wasn’t quite as smooth as I thought it was going to be. Maybe if you think back to when you started to where you are now, you probably have learned a few tricks.

Zibby: I used to write down all my questions ahead of time. I would do quotes like I was a kid in school and send all the questions. I did that for years until finally, someone came on and was like, “Why do you send the questions?” I was like, “Just to prepare and let you know.” He was like, “I think it would be a lot more fun if you didn’t send questions.” I was like, all right, that would save me some time. Then I stopped, but it helped for a long time. Not that you need that, but it helped me.

David: Mine’s called “Fail Better.” It’s about failure, the glory and necessity of it and that kind of stuff. I don’t know what it is.

Zibby: I don’t think of you and failure in the same breath.

David: I’m not just talking about myself. My sense is always, it’s never exactly what you thought it was going to be or what you had in mind, no matter what the creation is. That’s failure in art. There’s failure in life. There’s all different kinds of failure. I had this idea that I wanted to be talking about how to shift the perspective on failure as not something to fear, but something to embrace, in a way, because that’s the only way you move forward, really, or you can just do the same thing over and over and succeed at that. You can live your life that way if you want, but that felt kind of lonely and not a way to go. That’s just the vague idea that I have, the discussion that I want to have. I’m not saying your job is easy, but you’ve got the one book, so you’re going to ask about this. For me, it’s very hazy. It was an interesting feeling. Should I get back to what this is supposed to be about? But this is interesting.

Zibby: Well, it’s your show. You get to do whatever you want.

David: I forgot that in the moment.

Zibby:

David: It’s an Amazon limited series called Malice. It’s wealthy people behaving badly kind of a deal.

Zibby: That sounds good.

David: It seems to be what people want these days.

Zibby: I’ll take some of that. Do you write while you’re in the midst of acting, shooting, whatever?

David: I don’t generally. I find it hard, physically hard, just energy. Mentally, very hard to be able to shift focus like that. The only time I ever wrote while I was acting was when I was doing The X Files, but I was writing X Files, so it was same headspace in a way, even though very different motor skills than do one and the other. Generally, no, because when I write, I write hard and fast and focused. I’m not a slower writer who can do it over — I’m more of a sprinter when I write. I can’t be carrying something else when I’m sprinting.

Zibby: Got it. Now maybe you can just go back to a short story. We can get shorter and shorter until then you have poems. Just poems at the end.

David: I do have a bunch of poems that I thought about publishing just because it would make me seem like I’m being more productive than I am. These are poems that I’ve written over a lifetime, really. I don’t know. I’ve got to find somebody who would be interested in publishing them. There’s the literary poetry market. You sell twenty copies, and it’s a hit. Then there’s the popular poetry market, which I think is basically just Billy Collins and maybe Amanda Gorman. Then I don’t know what happens in between.

Zibby: I guess you could find out. Do you have any advice for aspiring authors?

David: The most obvious advice is just to sit your ass down and write. That’s it. It is a marathon. It is a muscle. It is a way of life. I may be tired.

Zibby: Oh, my gosh.

David: There’s nothing better than having done it. I would say that I don’t really love writing, but I love having written, when you come out of it. If you’re just in the space and you’ve been typing away for a couple hours and you realize, that was a couple hours where I was elsewhere, even if it’s a dark place, you’re doing dark work or whatever, it doesn’t matter. It feels like a vacation of some kind of just to be off the screen, for one thing, and be out of whatever the loop is of the news of the day and all that stuff. It’s just good to keep your own company.

Zibby: Very true. Thank you. You’re a beautiful writer. I really enjoyed the story and the conversation. Thanks.

David: Thank you. Likewise.

Zibby: Have a good trip.

David: Take care. Sorry I was late.

Zibby: No worries. Buh-bye.

David: Bye.

THE RESERVOIR: A Novella by David Duchovny

Purchase your copy on Bookshop!

Share, rate, & review the podcast, and follow Zibby on Instagram @zibbyowens