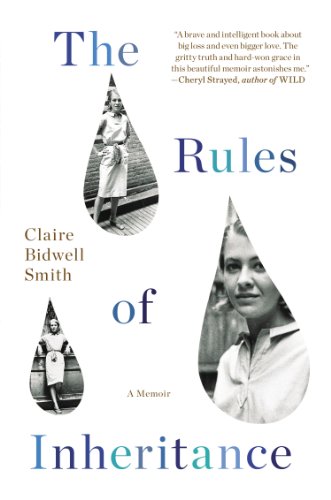

Claire Bidwell Smith, THE RULES OF INHERITANCE

I’m thrilled to be interviewing Claire Bidwell Smith today. Claire is the author of the amazing memoir The Rules of Inheritance. She also wrote After This: When Life is Over, Where Do You Go?, and most recently, Anxiety: The Missing Stage of Grief. The Rules of Inheritance has been published in eighteen countries and is currently being adapted for film. Claire has contributed to many media outlets including The New York Times, HuffPost, Slate, and many TV, radio shows, and podcasts. A graduate of The New School with a master’s from Antioch University, she is a grief counselor in Los Angeles. She lives in Santa Monica with her husband and three children.

Welcome, Claire. Thank you so much for being here. I’m really beyond thrilled to be interviewing you today. Thank you. Let’s start with you telling listeners who might not know what The Rules of Inheritance was about. We’re sharing this microphone, so for any delays, I’m passing this back and forth for technical issues.

Claire Bidwell Smith: I also need to mention that I have my three-month-old baby here. If we hear him, it will just add to the fun. Rules of Inheritance is my first book. It’s a memoir about losing both of my parents to cancer. They both got cancer at the same time when I was fourteen. I’m an only child. It was really challenging to go through all of that and feel really alone and set apart from my peers. My mom died when I was eighteen. My father died when I was twenty-five. I didn’t know anybody who was going through anything like that. Most of my friends were living normal lives, going off to college, on the usual trajectory that we’re supposed to go on. Mine was really skewed.

My mother’s death was really hard. She was my world. I loved her. We were incredibly close. She and my father had very different deaths. She really struggled to face hers and to come to terms with the fact that she was dying. She tried up until the end to go through various things. When she died, it completely floored me. I didn’t see it coming. My father died seven years later when I was twenty-five. His death was really different. He embraced it and really helped me to embrace it. It was a different experience completely. Throughout both of them, I was always writing. I’ve been a writer since I was a kid. As an only child, it was this internal thing I did. I read all the time. My parents were older. I got dragged around on a lot of trips. They were always having parties with grown-ups.

Claire: That’s my baby.

I had my nose in a book all the time. I started writing at a really young age. It became my outlet for understanding the world and making sense of things and myself. When they were sick and going through all of their things and then their deaths, I wrote through it all to keep myself sane. I had so much internally that it was helpful to get it out in writing. After my father died, I started writing even more. I was writing about him while he —

Claire: Oh, mister. I’m going to pick him up. You can ask me another question in the middle of that. I’ll keep adding on to it.

Zibby: You had such a beautiful scene, by the way, when you were with your father and he was like, “You just have to let me go.” I was ready to cry.

Claire: Hi. Is that better? You want to sit on my lap with me?

Zibby: I’m going to read a scene while you deal with your baby. We can come back to it. There were so many things I wanted to quote from your book. I want to start with this whole thing about grief. You’re this brilliant writer about grief. Now, you’ve dedicated your whole life to helping others get through it. After three years without your mom, you wrote, “In three years, my grief has grown to enormous proportions. Where in the very beginning I often felt nothing at all, grief is now a giant, sad whale that I drag along with me wherever I go. It topples buildings and overturns cars. It leaves long, furrowed trenches in its wake. My grief fills rooms. It takes up space and it sucks out the air. It leaves no room for anyone else. Grief asks like a jealous friend reminding me that no one else will ever love me as much as it does. Grief is a force and I am swept up in it.” Later after your father passes away, you write, “If grief was once like a whale or like a knife, it became a vast nothing, expanding outward from the very core of who I am.”

All so beautiful. The whole book was gut-wrenching and beautiful and addictive and amazing. Tell me how you feel your grief — you almost chart the waters of where it goes and its shape shifting over time. Can you tell me a little more about that and how you were so aware of your relationship with the grief as you went through it?

Claire: I wasn’t always aware of it. When I wrote that book, I was very aware of it. At the time that I wrote the book, I was thirty. I was newly married and had just had my first daughter. I was working in hospice as a grief counselor. When I started working in hospice, I began to see grief in a much more three-dimensional way. I’d always known my own grief. When I really started to see so many other people who were grieving, it was a different experience. I really began to understand it and understand my own journey and process through that lens too. It was really helpful in that regard. There was a lot of my journey in grief that I didn’t recognize at the time as grief. It was confusing. I thought I was angry or there was something wrong with me. I just tried to ignore it. As I moved through it and then later working in hospice and then really diving into the grief world, I saw all of my journey for what it was.

When I sat down to write this book, it’s organized around the five stage of grief: denial, bargaining, depression, anger, acceptance. I divided the whole book up into that. What I did was I sat down, and I wrote those five stages down. Then I wrote down three times I had been in each of them, so three times I had been in denial, three times I had been angry throughout my journey. It was born out of, again, working in hospice. People kept coming to me to talk about the five stages. They had a lot of confusion about them, all my clients and the people I was working with. They would come and they would say, “I don’t get these five stages. I think I’m stuck in one. I skipped one. I’m circling back to another one. Do I have to go through them in this perfect fashion?” I wanted to show how fluid they are and how they’re not that linear. My story became nonlinear as well, and these layers of grief that I went through.

Zibby: In your anxiety book, Anxiety: The Missing Stage of Grief, you mentioned how the stages were originally for people who were dying, not the people coping with loss and how there’s a lot of confusion about that and how anxiety should be a part of that but unfortunately is not. People often miss it in a way.

Claire: They do. I’ve written three books now. I’m a therapist specializing in grief. I keep seeing this confusion around the five stages. I’ve written about them in every book I’ve written. I love Elisabeth Kübler-Ross who coined the five stages. Like you said, she was originally intending them to be for people who were dying. They make a lot of sense in that regard: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. You go through five stages when you face a terminal diagnosis, not so much with grief. There’s more stages. They’re not this perfect formula. The reason that everybody clings to them is because we want a perfect formula when we’re grieving. It’s so hard. It’s one of the most difficult things we’ll go through.

He is trying to grab the microphone. It’s very cute. I just want to make it clear for anyone who’s listening what that noise is.

Zibby: You were writing a blog while you were going through all this. Let’s go back to Rules of Inheritance. Sorry to keep jumping around. You were writing a blog. The writing you did to help yourself, you were sharing with others. You said in The Rules of Inheritance that there was an article about the top twenty blogs at the time. Yours was one of them. Then I guess there was some demand for your blog to be a book. Tell me about how it went from blog to book. You had a lot of misgivings about it in the middle. How did it take this form?

Claire: I was an early blogger. They were still called web logs back then. It was 2002 when I started blogging, which is a long time ago. It felt like a natural extension of all the writing I had been doing in school. I had just graduated my undergrad.

Are you smiling at her?

I really missed writing, having somebody to be accountable to. I felt like a blog was a good way to do that. Then my father began actively dying. It became this really necessary outlet for me. I was writing all the time. All these people started reading it. I was writing this really raw stuff about my father. He died while I was writing that blog. Then a month later out of nowhere, The Sydney Morning Herald in Australia named it one of the top twenty-five blogs or whatever it was in the world. I got all these readers and attention and an agent. I got this big, fancy, New York agent. Right away this agent was asking me if I wanted to write a book. I was like, “Yeah,” but I was twenty-five. My father had just died. My story wasn’t done yet. I didn’t know how to do it. I kept up with it.

The story about Rules of Inheritance that a lot of people find interesting is that I wrote three versions of it. The one that is published and on shelves is the third and final version. I wrote the first two complete, full manuscripts. All three manuscripts are different. It took me writing it three times to really nail it. It took eight years. I just kept writing it. I kept coming back to this story. I feel like when people talk about writing books — they see this book. They’ve heard of it. They think it’s something I just dashed off like it was some easy thing. It was not easy at all. I really had to wrench this book out of me and write it many times to understand how to tell the story.

Zibby: Just curious, you chose not to use any punctuation marks. Was it always like that?

Claire: No quotations.

Zibby: I’m sorry. No punctuation…there’s no punctuation in the whole thing. There’s not a single period. I’m sorry. There are no quotes around any of the dialogue. It worked so incredibly well. You don’t indent. It’s almost stream of consciousness, poetic in a way in its form. Was it like that in all the drafts? Was that a later invention?

Claire: It was only the final draft that I did that for. The other ones are much more traditional. One of the big things that changed with this final draft was writing in present tense. That lack of quotations and the lack of indentations came with the present tense writing. It was very poured out of me at that point. The present tense is what makes a lot of things about this book work the way it does.

Zibby: Just to be clear, yes, it’s about losing your parents, this book, but you have so much more in there. In the beginning, you talk about when you went away to college. Of course, you did it to show the juxtaposition of what happens after your mother’s visit. Even how you wrote about your mother visiting you in college, you said, “As the weekend went on, my mother grew too loose with me. She let me ignore her, let me smoke cigarettes in her rental car, and invited my friends out to dinner with us on the second night. She seemed desperate for me to let her in. I had only just discovered how to be without her. Why would I want to let her in? On Sunday, I watched her drive away, my lip between my teeth, blood on my tongue from the force of it.”

It clarified for me, “Why was I rude to my mom all college?” You have this way of getting into each moment in life, not just the loss. It’s so complicated, especially mother-daughter relationships, separation anxiety and the whole thing. That passage, I was staring it and turning down the page. Yes. That’s it. You finally learned to be independent, and it feels so tenuous that you can keep it that way.

Claire: It’s still brutal to look back on sometimes, especially being a mom now. I have an almost ten-year-old. She has these moments where she just pushes me away. “I hate you, Mom,” because I won’t let her wear sweatpants to school. I flash back on all that time with my own mom. I wasn’t aware of being like that in the moment. It was only later. It came so fast when she died. The moment she died, all of a sudden, our relationship was finite. It was over. All these things, the ways I could’ve repaired that or apologized for it or come through in a different way later on, all of that was lost and gone. I couldn’t help but review our relationship and all those moments like that. They ate me up for a long time. Writing about them helped me to release them and to forgive myself as well.

Zibby: In your third book, Anxiety, you give advice to people like write a letter, how to address the guilt that you feel. There’s also obviously a lot of guilt for what isn’t said or how you handled it. In The Rules of Inheritance, I wanted to give you a hug. You were beating yourself up so much, like on that drive down. Oh, my gosh. That passage was insane. I read it out loud to my husband. I was like, “Listen to this.”

Claire: It’s one of the things I see in grieving people more than almost anything. I haven’t really come across anyone who hasn’t walked away from a loss without something they feel guilty about, something they wish they could go back and change or do differently. Those things can really eat us up. Even though that relationship is over in many ways and we can’t actually go back and change things, we still work through it internally. We can work through it. We can make amends. We can make amends within ourselves and even with those people, maybe spiritually. There’s a lot there.

Zibby: I lost my best friend on 9/11. She was my roommate and closest friend. We were twenty-five when she died. I ended up taking her mom out to lunch and apologizing for some of the things that happened over the course. There’s no way to tell the person you’re sorry. “Hey, I wish I hadn’t handled things so immaturely when you were staying at my mom’s house that time. I wish I had called you more than twice when I went to business school,” all these things. I just sat with her mom. I was like, “Here are things I’m sorry for.”

Claire: That’s beautiful. We have to be able to do that, otherwise those things live inside of us. They fester. We have to let them out.

Zibby: It was great, your advice. Getting through the memoir and then you have this companion — I didn’t read your other book yet — companion to getting through. It was so great. You also do a really beautiful job of talking about what happens when you’re in a really unhealthy relationship, which could be its own book, honestly. It was so good. The way you write about relationships in general, like with this boyfriend you had early on, you said — actually, he wasn’t even really a boyfriend — “I feel like I’m constantly on the verge of scaring him off. I stay still, make no sudden movements. I am careful with my sentences. I am always amazed that he is still sitting there.”

That was such a perfect way of that insecurity you feel around some people you’re with, almost like you’re going to jinx it if you say the wrong thing. You had idolized this guy on the motorcycle and the whole thing. Later on when you get into this, not abusive but very unhealthy situation, and the way you write about that and finally your ability to break through it, that is, in its own, an inspirational book. I was also wondering as I read it, did he ever read it? Was that his real name? Did he read it? What happened after? Did he?

Claire: I don’t know if he’s read it. He’s here in Los Angeles. I haven’t seen him in years and years. I changed his name.

You want to take him? We’re passing the baby.

I changed his name and some of his identifying characteristics, nothing that changed the story at all, but to keep him from suing me, which is something that you go through after you write the book. That was an intense relationship. He had been through his own grief. I had been through my grief. We were living in Manhattan together in our early twenties. We were a hot mess, drinking all the time, in pain all the time. There were beautiful things about that relationship too. It’s such a dark and twisted relationship and so unhealthy. I know it’s painful to read from the outside as well. When my mother died, I just felt so alone. He was this person that understood this hole inside of me.

Are you smilin’ away at me?

There was a lot of beauty in it too. The way the book is arranged, since it’s told out of fashion, you don’t actually see us connect and fall in love until towards the end of the book. You’ve seen a lot of the darkness in that relationship before you actually get to the sweetness at the very beginning of it, which I think was an interesting way to do it. It somehow made sense to me to do it that way.

Zibby: Then you also later show, not that it’s the way out to help other people, but you did show that after you got to a place where you were helping others when you did the tutoring, and then helped with Dave Eggers’s project in LA, how giving back made you —

Zibby: I’m sorry. The baby’s squirming.

Tell me how the act of throwing yourself into helping others took you out of your grief for a little bit.

Claire: That was the thing that really saved me. I felt so empty and purposelessness. Life felt very meaningless after my parents died. I was so deep in my depression. I couldn’t figure out what I was doing, what the point of anything was.

He looks so happy. He’s sitting on Zibby’s lap looking so happy. She’s bouncing him as I talk.

I knew Dave Eggers. His book, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, had come out around the same time. He was a few years older than me. He had also lost his parents. I was like, “Perfect. We’re going to get married. He’s a writer. He’s cute. I’m a writer. Our parents are dead. This is going to be great. We’re going to totally get married. Everything’s going to be perfect.” We did not get married. He married a lovely woman named Vendela Vida. I did end up working for him though. Because I thought we would get married, I was following him and following his work that he did. He’d opened a nonprofit tutoring center that works with underprivileged and underserved school systems.

I ended up working there really just intent on trying to marry Dave Eggers and then found that it completely changed everything and healed me to be giving of myself and working with these kids. I was getting up in the morning and having a place to go and something that was worthwhile of my time. It was the thing that finally pulled me out of my depression and gave me purpose in life again. I’ve never gone back from there. I went from that job to working with homeless people, went from there to grad school. Out of grad school, I worked in a lot of underserved mental health clinics. I’m in private practice now. Now, it’s become a huge part of my life to be of service in some way all the time.

Zibby: The Rules of Inheritance is maybe going to be a film?

Claire: Jennifer Lawrence picked it up right away, even before it had even come out on the shelves. She read it. She loved it. This was right before she won the Oscar for Silver Linings. She was famous, but that same time she really hit it big. It was amazing. There was a whole deal that went through. I talked and met with her many times. She was great. There was a writer, a director, producer on the project. Then it just, as things do in Hollywood, it eventually fell apart. She got really busy. The screenplay had trouble. It all fell apart. It was fine. I was never quite sure about the whole movie aspect of it. It’s still circulating. Emma Roberts was more recently interested in it. I’ve been trying to adapt the screenplay myself at the urging of my film agent. I’m not a screenwriter. This book is really hard to adapt. It’s a tough one to put together in a screenplay. It’s always simmering, but not currently.

Zibby: Do you have plans for another book?

Claire: I don’t know. I’ve written three books and had three babies. They’ve all come together. I’m nervous to start another book because I’m worried it’s going to get me pregnant somehow. I don’t know if I can write a book without having another baby. I don’t want to have any more babies, even though you’re so cute. I have so many babies now. Of course, I will definitely write another book. I don’t know what it is yet. Each one I’ve written, there’s kind of a postpartum period where I need to let the book be out in the world.

Claire: Is that funny?

Often, whatever shape that book takes and all the things it brings into my life and the opportunities and the people I meet, that usually informs what the next book will be. My second book, which was about the afterlife, I got more into the grief world. I started hearing a lot more from people. That’s when I started to see all this anxiety. That was the next book. I’m not sure yet what’s coming. Relationships are a big one. People keep talking to me about relationships. I’m very interested in relationships. I’m on my second marriage now and have stepchildren. I see how much relationships are impacted by grief as well, how much those things change with the grief process. That might be the next book.

Zibby: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

Claire: Oh, my gosh, just to write all the time but to not overthink it. People sit down and they want to write a perfect first sentence, a perfect first paragraph, the perfect book. It’s never that way. I threw away two entire books that I wrote before I could get to this one. I’m grateful to them. I couldn’t have written this version without having written all the bad versions. We have to be patient and diligent and keep writing, writing and writing and writing.

Zibby: Thanks to you and Everett for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.” Do you have anything to say, buddy? What do you think?

Claire: Do you want to talk? Oh, you want to eat the microphone. No, we’re not going to do that.

Zibby: Thank you so much for coming on.

Claire: Thank you.