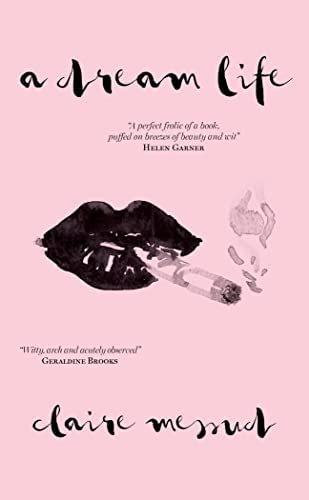

Claire Messud, A DREAM LIFE

Author Claire Messud joins Zibby to discuss her latest novel, A Dream Life, which she actually wrote years ago before abandoning it at the recommendation of a mentor. The two talk about Claire’s original inspiration for the story, as well as who she believes most readers will connect with, and the main misconception about novellas. Claire also shares her journey to becoming a writer, why her famous novel, The Emperor’s Children, was almost never written, and the semi-autobiographical project about her family she is working on next.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Claire. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books” to discuss A Dream Life and your whole life and The Emperor’s Children and everything else. Thank you.

Claire Messud: Thank you, Zibby, for having me. It’s great to be here.

Zibby: I was so excited when this new book came out because I read The Emperor’s Children with my book group before I did any of this stuff when I was just a hardcore reader, which is what I usually was. I remember that so well and just having the book next to my bed for so long and delving so deep into those characters. I remember scenes in my head. I was very excited when your new book came out, especially because it’s not even a fraction as long as the last book.

Claire: There have been a couple books in between. This one is short. In fact, I think they call it a novel, but in my mind, it was a novella. I’m a big believer in the novella. I don’t know if you are, as I am, a fan of Alice Munro, the short story writer. She certainly, at one time, said, I pity novelists because I fit everything I want to say into thirty pages, which seems the ideal. A novella’s a bit longer than that. I feel like, how great if you can fit a whole novel into a story. Wonderful. As a reader, I really love a shorter form. I do.

Zibby: I was actually just talking last night — I did an event with Annabel Monaghan, who wrote Nora Goes Off Script. She said her first draft of that was ninety pages. She told all her writer friends, she’s like, “I wrote my novel. It’s done. It’s ninety pages.” They’re like, “That’s not a novel.” Then she said she went and bought The Bridges of Madison County and was like, “That’s ninety pages too. Everybody read that book. That was a book.”

Claire: Right. Who gets to decide what’s a novel? What’s not a novel? I think that about all sorts of categories that seem to me more about publishers trying to reach readers rather than about the things themselves.

Zibby: Also, nobody has time these days for anything. If we’re going to argue for reading, which I am, then how great to have a shorter alternative which is just as impactful. Who’s to say that’s less valuable? It might fit in more with your lifestyle. If it’s reading and it’s a story and it’s a connection, labels aside.

Claire: I’m with you. I’m totally with you. Is a meal better if it’s a bigger?

Zibby: I mean, yes.

Claire: Not necessarily, right?

Zibby: No, I’m kidding. No.

Claire: It really depends.

Zibby: It’s true. It’s not always better. No, especially lunch. I don’t like big lunches. Anyway, why don’t you talk about where this particular novella, novel, whatever we want to call it came from? Why write this now? Your general oeuvre.

Claire: The extraordinary thing is that I didn’t write this now. About twenty years ago, I published a book of novellas. There were two novellas in that book. In my mind, there were going to be three. Then I had given this to someone to read, to a writer who was older and more established and who was very nice. He said, “It has no plot. Not enough happens.” Then I was ashamed of it. I didn’t show it to my agent. I didn’t show it to my editor. I put it in a drawer. What happened, which I find sort of serendipitous, is that a couple of years ago, Jemma Birrell, who set up Tablo Tales — I had met her because she used to run this Sydney Writers’ Festival. She had invited me to attend that now eight years ago. She wrote. She said, “I’m doing this thing. You wouldn’t happen to have a short-ish novel? Who has a short-ish novel in the drawer?” I was like, who has that? She said, “My hope is that people will be willing to do this and donate the proceeds to charity.” She was in Australia. I had this novella in a drawer or novel in a drawer that was set in Australia. I was like, what are the odds? I said, “Listen, see what you think. You may feel, as my friend did all those years ago, that it doesn’t have enough plot or whatever. If you like it, I would love to give it for this venture.” The proceeds all go to saving wildlife, to the Wires Rescue. It’s an organization that saves wildlife from the wildfires in Australia, which are a really bad scene.

There is, for me, this funny thing that it isn’t of just now, but it’s still — when I took it out of the drawer and read it, I was like, oh, I still believe in this. I still have my heart in this. That’s, in part, because it’s based a little on my childhood. It’s trying to imagine what it was like for my mother as a stay-at-home mom in the early seventies. In that time, many a wife and mom packed up and went where her husband’s job took them and had to begin again. I think for my mother to be told, “And now we’re moving to Australia,” was really like, what? That’s fifty years ago, basically. It really seemed far away. The telephone calls were difficult. Travel was very lengthy and expensive. It wasn’t quite like 1800s, setting off on a sailing ship, but it was really a huge move. That’s what I was trying to imagine. What was that like? It’s a fictional character. It’s not my mom, but for somebody like that to be leaving behind everything they knew and all the context, all the threads that make you who you are or that you believe make you who you are, the connections and the friendships and the deli that you know and the post office that you use and the doctor who’s been your doctor since you were eighteen, all those things vanish. You’re beginning again. In this case, she sort of gets caught up in inventing a persona that isn’t necessarily that close to who she might otherwise be.

Zibby: I feel like travel in the “olden days,” it was like you were off the grid completely no matter where you were. We would go away for spring break, and I would be like, I can’t wait to reunite with my friends. I would get off the airplane and run to the closest pay phone and call them from the pay phone. Why couldn’t I have just called them from wherever I was? I don’t know. There was something about being home. Then you could be in touch again. Sometimes I’m even like, I can’t get in touch with so-and-so because I know she’s traveling to Italy. Then I’m like, she’s probably checking her email every two seconds anyway. There’s still that lingering, oh, she’s away. Do you still have that?

Claire: Totally. It’s true. Anytime a friend leaves the country, I’m like, well, I’ll text her when she gets back. She still has cell service in Sweden. Come on.

Zibby: I know. It’s exactly the same. I can’t seem to let that one go. Your character, she also has this massive house to take care of. They move into this beautiful place that is really hard for her to manage herself. She has two kids, right?

Claire: Yes.

Zibby: I read this a little bit ago. She has two kids. She has this massive house. She’s trying to find a house cleaner and randomly recruits this young girl who doesn’t know what she’s doing either. It’s also, the trappings of privilege doesn’t always make it so great. You think from the outside, maybe, that having this massive, beautiful house is so perfect. It’s overwhelming. She can’t manage it. She can’t keep it clean. She’s really stressed out. Yet to others, it looks like the perfect life. I love that peek inside to say, nothing is just exactly what it seems. You don’t know what’s going on inside anyone’s house.

Claire: Totally. For me, in my head, part of the story was that the people she comes to know best or encounter most are the people she’s employing to help her. She’s building this kind of fortress around herself. The house comes with a gardener. They have to employ the gardener. She doesn’t really get on with the gardener so well. Then as part of her husband’s job, she has to give parties, so there’s a caterer.

Zibby: Right. Oh, yeah. The tent, they were fighting.

Claire: The caterer is super bossy. The caterer’s like, we’re going to do this. The gardener’s bossy. Then she hires this housekeeper to live in who she thinks, wow, this one, she’s great. She’s going to be my friend. They are friends, but that woman’s totally her own weird person. For me, in my head, that woman, whose name is Simone, she’s living much more the life she wants. She’s living life on her own terms, not necessarily fully straightforward terms, but she’s totally living life on her own terms.

Zibby: She leaves soon too. Didn’t she? Didn’t she leave?

Claire: Yes, she leaves too. She literally leaves in the dead of night. The idea is, how terrible she’s not fulfilling her role. In my head, at the same time, she’s not fulfilling her role, but she’s doing her thing. Whereas Alice, the main character, she’s pretty constrained by all of this stuff and has been made by all of them, by convention — all of these people are like, this is what you need to do. You need to hire a housekeeper. You need to do this. You need to have this kind of party. You need to wear these clothes. I feel like we’re all of us, in our lives in varying degrees, involved in versions of that. I’m, interestingly, just reading a novel that’s been translated from French by a woman who was a lawyer. She comes from a very fancy French family. She was a lawyer, married with a child. At some moment eight years ago, she chucked it all over, including being a lawyer. She’s now queer. She cut off all her hair. She got tattoos. She lives on the margins in a tiny studio and hardly has enough money. All of the things, like nice clothes and — she just chucked it over. It’s so interesting to read that because you realize, wow, that’s really courageous, not just for herself, but in the eyes of the world. We’re always navigating both our inner selves and then the eyes of the world. What would it mean to live in that big house and let the weeds grow up to six feet and the windows get really dirty and never wash the laundry? What would that mean? Everybody would be whispering.

Zibby: I think only certain personality types could handle that. I would not be able to handle that. That would give me so much anxiety to see all that dirt. I would just be scrubbing.

Claire: Me too. It’s a really interesting question. Would your five-year-old self have felt that, or were you sort of trained? Is that an innate

Zibby: Actually, I think I was much more comfortable with mess when I was younger. I have this distinct memory when I would come in in the summertime and throw my towel somewhere. My mom would say things like, “You have to take care of this house. You can’t just throw your towels everywhere.” I’m like, “But it’s our house. Why can I not put my towel somewhere? Don’t we live here? Why does it have to be so perfect all the time?” Maybe I’m going to scratch that and say this is something I’ve created. I’ve created my own monster.

Claire: Or a series of circumstances, parents, school, college, life. Also, when you have to deal with the mess yourself, it’s like, no, that’s not nice. I don’t like it.

Zibby: To your point, you are very much judged. If somebody were to come over and your house was filthy and unkempt, that would be a reflection on you.

Claire: Yes. My house is a total mess.

Zibby: It is not. I’m looking at your room.

Claire: I make a distinction, though, messy and dirty. I’m not dirty. I’m just messy.

Zibby: That’s totally different.

Claire: It’s totally different. There are piles of books everywhere, but I dust the piles of books.

Zibby: That’s great. That’s just aesthetic. That’s an aesthetic choice.

Claire: I’m all for clutter, mess, but we’re reading. I don’t know if you’ve cited it before. There’s a wonderful line from the writer Rebecca West about a hundred years ago. She said a house unclean is better than a life unlived.

Zibby: I like that, yes. You can get caught in the trap of just — it’s almost like a navel-gazing if you’re just too much cleaning and making things perfect. Then how do you break out of that and be unpredictable and come out with a novella, perhaps?

Claire: I loved stories as a kid. I loved being read to. Then when I could read, I was like, oh, my god, I can read. I can just take the stories and run. I was always the kid in the back of the car reading. I remember my mother yelling at me because she thought I was sleeping in. She thought she was being really nice and letting me sleep in, but I’d been awake since six in the morning reading a book in my bed. I was that kid. When I discovered pretty early that stories were not like rocks and trees, they hadn’t always been there, that people made them up, I was like, oh, that’s a thing we can do? Then the question was always, how do you find a way to eat and have a roof over your head and do that? Still working on that.

Zibby: What was your first break?

Claire: I wrote my first novel — I’m an MFA dropout. I had started as an undergrad, some stories about some characters. Then I was turning that into a novel. I started an MFA. It was at Syracuse. My now husband was in London. I was lonely. Back to the pre-internet, it was far. It was hard. I dropped out and went back to London. I got a job. I feel like this was really the moment of great good fortune. I got a job working on a newspaper, The Guardian newspaper. I was a junior person on what was called — I don’t know if it still exists — the Women’s Page, which wasn’t recipes and knitting. It had been started in the twenties as a feminist thing. It was very interesting. It was interviews with politicians and peace activists and also writers. My editor was not that interested herself, so she handed me the writer stuff. It meant that I got to know a bunch of publicists and editors around town because they were pitching to me for pieces in the newspaper. When I finished my novel, there were several of them who’d said, I’ll have a look. The woman who’s still my British editor, who’s about my age, liked it, my first novel, well enough to publish it, which was wonderful. At that time, she and my agent were going out. I always think that if they hadn’t been going out, I would never have been published.

Zibby: That’s so funny. Just because I remember loving Emperor’s Children so much, tell me about writing that and the process of that book and weaving together all those different — how did you go about that? Is your process the same? Does it course through all of the books, where you write, how you write, all of that in terms of process?

Claire: That book — I had started a novel. I was really struggling with it. I had a baby. In July of 2001, I had a baby. Then in September of 2001, there was 9/11. My novel, which was set in New York about young people, it was like, wow, I can’t write the novel I thought I was going to write. There was the better part of a year where I didn’t know whether to write fiction at all. I also had a little baby. She’s turning twenty-one next week. I started some things. My husband, usually, he’s just like, keep going. He doesn’t say, at the beginning, that’s terrible, usually. With the stuff I was starting at that point, he was like, don’t continue with that. Don’t. No. No, not that one. There were three totally aborted attempts. Then I went back to these characters, and I started again. In a funny way, I had more compassion for them because I felt like history dealt this hideous blow. Yeah, maybe they were self-absorbed or kind of vain in certain ways or whatever, but we’re all people. I didn’t need to be satirical. I feel there are satirical elements in the novel, but I didn’t need to be satirical. I had compassion for them. They were totally real to me, I think made more so by the tragedy of the world. The thing I would say about writing it is — then I had another child. You know how it is. I don’t even remember. I was writing little dribs and drabs. The characters in that novel are really short because I could manage a short chapter. I could keep my focus on it. Before, I’d always been somebody who wrote, and then I’d go back over it and over it. By the time I finished it, there had been forty drafts of something. No. This was just like, I got to keep going. I got to keep going. I write by hand in a notebook.

Zibby: Wow. Still?

Claire: Yeah, still. I just had to keep going forward. That was useful because I think with kids, you have to do that. You don’t have the luxury of time in the same way. For a really long time, you don’t have the luxury of time in the same way. Maybe in the digital world, we never again have the luxury of time in the way that we did.

Zibby: Don’t say that, please.

Claire: You know what I mean, right? There’s so much. We’re all bombarded with so much. It was a good training for me to learn you can just keep going. The world doesn’t fall apart. It’s okay.

Zibby: I feel like the scene that I remember the most vividly is this dinner party scene and getting ready for a dinner party. Did I make that up? Was that in the beginning of the book?

Claire: I don’t know. I don’t remember.

Zibby: I’m going to have to go back. I have this whole apartment in my head, and a couple and this whole pre-dinner party preparation.

Claire: It could be. It’s not

Zibby: Maybe I’m wrong. I’m going to go back and look. I don’t know. I shouldn’t even have said anything out loud.

Claire: No, it could well be. I have the memory of a sieve. It’s a long time ago.

Zibby: Thanks for going easy on me. What project is next for you? Then I’ll let you go.

Claire: Thank you for asking. I am in the middle of a novel that is sort of based — I’ve never written anything autobiographical before. It’s not autobiographical in the sense of being about me. It’s a novel that takes the trajectory of my father’s life. It’s fiction. Stuff is made up. His life was odd in the way I think of many twentieth-century lives. The world he was born into — my father’s family was pieds-noir. They were French colonials in Algeria. He was born in 1931. Then there was the war. Then after that, there was the war of Algerian independence. By 1962, Algeria was independent, as absolutely should have happened, but what it meant was that a lot of people were displaced. What they thought of as home no longer existed. The world that they thought of as home was a vanished world, which happened to so, so many people in more dramatic circumstances, of course, in the twentieth century. This gave me an almost coat hanger frame on which to build a story or shape a story. Of course, here I am. I’m an American person. My frame of reference for everything is so far. He traveled from that world to — he died in Stamford, Connecticut, so it was a long journey. As he was near death — he was not religious, but my aunt was very religious. She wanted somebody to come and give him the last rites. He said to me, “Is there somebody who could do it in French?” The last time he’d had any religious involvement, it was when he was young and in French. I said, “I don’t think so, Daddy. I don’t think I can find somebody.” That arc, to me, it feels so common of this era. We all move around.

Zibby: Wow. That sounds amazing. Thank you, Claire. I want to post a picture of us wearing our identical glasses. I feel like we should be on the Caddis website or something as sponsors. Anyway, it was lovely chatting with you. Thank you so much.

Claire: Thank you for having me. Thank you so much.

Zibby: Thank you. Have a great day.

Claire: Take care. You too. Bye.

Zibby: Buh-bye.