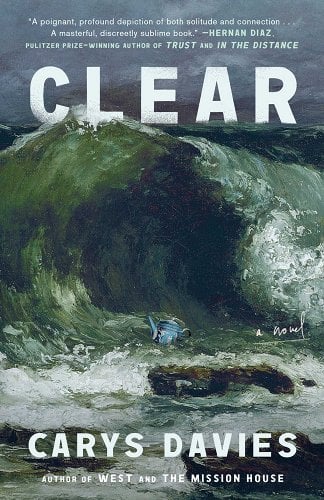

Carys Davies, CLEAR

Award-winning writer Carys Davies joins Zibby to discuss CLEAR, a stunning, exquisite novel about an impoverished Scottish minister who is dispatched to a remote island to “clear” the last remaining inhabitant… who has no intention of leaving. Carys reveals how a chance encounter with an extinct language dictionary ignited the spark for CLEAR over a decade ago and then discusses the profound impact of early photography, the extinction of the Norn language, and the socio-political landscape of 19th-century Scotland. She also describes her writing process and shares valuable advice for aspiring authors.

Transcript:

Zibby: Welcome, Carys. Thank you so much for coming on Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books to discuss your novel, Clear.

Congratulations. Thank you for having me. This is a beautiful work of literature. I mean, it really feels like that. Like it's, it's almost a surprise it's coming out today. I mean, it feels like it could have come out a hundred years ago. I don't know when. I mean, it's like timeless. There's a timeless story beautiful quality to it. And it's very impressive. So anyway, just thought I'd start with that. Can you tell listeners what your book is about?

Carys: Sure. So Scotland, 1843 and Scottish landowner Henry Lowry is evicting small tenants from his estate to make, make the land clear for sheep grazing. And when an impoverished newly married, uh, Presbyterian church minister, John Ferguson comes into his orbit looking for some paid work, uh, Lowry reckons that Ferguson could be just the man to clear the last remaining inhabitant of a very remote, small island off the far north coast of Scotland, which belongs to the estate.

And although John's wife, Mary, has misgivings about the whole task. Um, she really isn't at all sure that John should be going off to do it. They say their goodbyes at the gloomy granite harbor in Aberdeen and John sets off armed with a month's worth of provisions. Uh, the official summons of removing in his pocket and a pistol he's been given, but he hardly knows how to use.

And needless to say, things don't go smoothly.

Zibby: I love this idea of the, the picture of his wife when he falls and then how I'm not explaining this right. Hold on. Let me get their, let me get their names right. But basically, and it's not a daguerreotype, it's another kind of photo that I wasn't even as familiar with that you described.

What was it?

Carys: It's called a calotype. Essentially, I mean, a very early kind of photograph that had, uh, just been developed. And actually when I, when I first, uh, so yeah, so. What happens is that, well, I don't think it's too much of a spoiler to say there's an accident, and this calotype that John is carrying of Mary, uh, gets lost and is found by Ivor.

And when I was first sort of feeling my way into the story, I wrote this scene and it was a sort of, it was a miniature of, of Mary that I imagined Ivor found, finding. And then, and this is the really extraordinary thing I always find that happens with historical fiction. Once you're, You know, you've landed in a moment in time and suddenly everything seems to sort of converge on.

So I was in this year, 1843, and suddenly everything seems to be happening in that time. So I look, I was looking at the development of early photography in Scotland, in Edinburgh, and there were two pioneers, David Hill and his, his young partner, and they were developing this, this method called the, the Calotype.

And the idea that Ivor would be looking at, Ivor's the, the inhabitant of the island, would be looking at a photograph, you know, somebody who's lived like him in this immense solitude. I just thought that would be so powerful to see this thing, which looked sort of like a physical two dimensional person was very powerful.

Zibby: Totally. I know it's in the scene. It's like, he's like, this is more real. And his, you know, wife or, you know, his mother. I don't know. It's like the, I mean, the idea that you, that you could have gone your life without having seen a photograph and then see why that's wild. It's a wild thing.

Carys: Yes, well, same.

I mean, he, because he's been alone now for, um, he's in his forties. He's been alone since he's, he was in his early twenties, his mother and his grandmother and his sister in law for the last people to leave the island. So, you know, this, this photograph is so much more real than, than his memories now of the people that he loved.

Zibby: My goodness. Well, just the way you write, I mean, not, I think the accident was so early on. It's, I mean, but the way even you write about pain and broke, you know, a broken ankle or just all these little details that you, you give for each of your scenes makes them. Jump off the page and tell me a little bit about Your training in writing and then how you arrive at a story like this about a moment in time Like why this moment in time why these people like how did your imagination go there?

Why this book? I don't know. It's a marvel, but tell me more.

Carys: Well, so the, I'll take the first part of the question. When I began to write fiction, I began to write short stories. I was actually living in the United States back in the back in the early nineties and I began reading all the great American short story writers, Fanny O'Connor, John Cheever, Eudora Welty, Grace Paley.

I was completely blown away. I hadn't read them before and just thought, this is it. This is what I want to do. I was, I was really drawn to that, that, that, that concision, you know, there's so much power in, in brevity and what's between the lines and also that, you know, especially somebody like Flannery O'Connor, you know, that mix of, of tragedy and comedy, um, and pain and joy.

I thought this, this is where I want to be. So for the first couple of decades of my career, I, I only wrote short stories. And when I wrote my first novel West, I thought it was a short story and it was the longest short story I'd ever written. It was about 10, 000 words and then I sort of put it away in a drawer and thought, yes, that's finished.

And then I got it out a few months later and I thought, how could I have thought that that works as a short story? It just doesn't. It's sort of, it feels both overburdened and abbreviated. It's just, I love the story, but I knew I needed to tell it in a, in a different way. So I started writing a novel.

I didn't know how to write a novel, but, um, I sort of taught myself and it was, it was a really thrilling experience. It wasn't, I mean, I don't approach my novels differently from the way I. approach to short stories. It's just that every story is as long or as short as it needs to be, and you just have to sort of feel your way into that.

So I think writing short stories for so long, I think, you know, my, my craft developed in such a way that it's, It makes me a certain kind of writer and I still love the power of brevity and concision and sudden changes and juxtapositions and all those things. And this, to answer the second part of your question, this story, Came in quite an unusual way.

I mean, I do, I do believe that you can't really go looking for stories. You know, they, they find you, you don't find them, but with this story, it happened about 10 years ago, I was working in the lovely old reading room in the library in Edinburgh. And I got up to take a break and I was browsing the shelves and I found this old dictionary.

And it was a dictionary of an extinct language I'd never heard of before, called Norn, which used to be spoken on the islands of Orkney and Shetland in the far north of Scotland, there, off the northeast coast and the islands used to belong to Denmark and then in the middle of the 15th century the Danish king pawned the islands to Scotland and slowly over the century this old language was pushed out by Scots which is a kind of dialect of It's sort of English, Scots, it's a different, different language.

And so over a 10 year period, I just went back to this dictionary over and over again, because I just loved the words, they were so rich and so specific, you know, so many of them described the sea and the clouds and the fog and the weather, but also a kind of almost feudal way of life. And I knew there was a story there, but I just didn't know what it, what it was.

But eventually I realized I could sort of see Ivor, I could see this man on an island. I knew he was alone and I knew he was probably the very last speaker of this extinct language. And I thought that conceivably this could put him somewhere in the middle of the 19th century, which then led me into the whole history of, uh, what was happening in Scotland.

at that time where the land was being cleared by the big landowners to make way for sheep, and people like Ivor were being evicted from their homes. So that's how it happened, but it was always, it's a novel. I really wrote the story. A lot of the research sort of did afterwards. I think with historical fiction, you've always got to be careful not to just get too swamped in, in research.

So I prefer to try and grasp what's, you know, what's sort of fleeting and intimate and human and emotional first, you know, grasp that. And so I wrote this. book really out of the words in, in the dictionary. That, that was what I used to try and get myself into Ivor's head and create his story. Island and his life and the way he is, his fierce attachment to the place.

Zibby: When you're writing, how much do you go back and revise later versus making sure every sentence is right? Because every sentence feels quite deliberate.

Carys: Yeah. I mean, it's a very, I never used to know what writers meant when they sort of talked about, when I did this draft and then I did this draft and this draft and this, it never really feels like that to me.

It feels like total chaos until it, until it doesn't. And then, and that usually comes when I know how to begin and that came with this, this book starts with where John is, is in a storm and he's approaching the island. And once I'd written that scene and he was there. Then, I wrote the rest of the book in a, in a very sort of intense period of a few months, but I'd been thinking about it for, as I said before, for about 10, about 10 years.

So, and then yes, and then I just, I go over and over and back and back. And then finally, when I'm still sort of You know, fiddling with commas and, and then I think, okay, I think, I think it's done.

Zibby: Are you at work on anything else now?

Carys: I'm always, I'm always at work. I'm always thinking about stories. I, I always have a few things sort of bubbling away at once.

And just, I'm at that, and before one sort of, you know, comes to the surface and, and, you know, you know, announces itself as, as the one. So I, I think I know which one that is, but I'm still at the slightly sort of bubbling away state.

Zibby: Sounds good. Do you have advice for aspiring authors?

Carys: It's so hard to say, you know, be, be patient, but really, you know, it's, it's a marathon, not, not a sprint.

You know, I know some writers do, but it's, They write a book, it's their first book, and it's, it's fantastic and that, but that was not, you know, not my experience. It's been a very kind of long road. But, you know, just try and just read and read and read and, and learn and just know that, you know, those periods of.

of despair where you feel you're not getting anywhere. That's, you know, that's all really is. Nothing is wasted. You know, you are, you are making progress even when you absolutely feel like, like you're not. So you, you just have to keep doing it. There's no other way. And, you know, you have to be patient on the page and you also have to be patient in terms of where you feel you're going professionally, you know, and try not to.

Think about that too much.

Zibby: Is this where you thought you would be at this point in your life?

Carys: I don't know. What, what did I, what did I think? I didn't know. I don't think I ever really dared hope. I, I just sort of, I really did just go from story to story and, you know, each little success was such a, I remember, you know, when, when I was writing short stories, if I got one short story published in a year, that would, that was absolutely enough to, you know, to, to keep me going.

So. Yeah, I don't think I ever had a vision of what shape life would take, you know, you just take each story and try and make it the best it can be and, and hope that somebody might be interested in reading it.

Zibby: And I think I read that you were a judge of the, New York Public Library's prize, the young lion's prize.

How was that? I was a young lion for many years for myself. Now I'm an old lion, but I was at one point a young lion.

Carys: Right. Well, it was, um, no, judging is, judging is always, uh, I, I really, I really like judging and I take it very seriously because, you know, winning a prize or even being shortlisted or any of those things, it's such a huge, it means so much to a writer.

Any stage in their career. So I do, I do take it, I take it very seriously. And, uh, that's always a, it's always a real privilege.

Zibby: Amazing. I judged one thing once and I was like, Oh my gosh, I didn't realize this was so much work. It's so much work.

Carys: No, it's, it is. It's an awful lot of work. And then, you know, you know, you're, you're always comparing apples and oranges too.

I mean, so I'm judging a prize at the moment, you know, and, and, uh, it's, You know, a lot of 800 word, 800 page novels and then very slender ones. And it's, I think in the end, I sort of, I think a book has to sort of, you know, give me a shock to the head and the heart. You know, that's, that's all I can say. And it's, it's the one that sort of probably does the best job of that, but yeah.

And, you know, and then you, you know, you discuss it with your other judges and sometimes you realize that you haven't given something. Quite, you know, the shock that you should have. And then you go back and, uh, you know, change your mind and yeah.

Zibby: I love what you just said that a book has to give you a shock to the head and the heart I mean that is all we're looking for that is a summary of of what a good book does So good to have a synopsis Not a synopsis a clear sort of, you know target Are you reading anything now that you really love?

Carys: I just, I, I'm in a book club with some friends in, uh, in New York and LA actually, which we, we sort of have, uh, uh, kept going all the way through the pandemics. It's always on Zoom and, but we only read dead writers. So this last, uh, in fact, yes, just yesterday we, we did the prime of Miss Jean Brody, which, um, um, All of us had read as teenagers and, you know, now we'd come back to it and it was so extraordinary because we'd all remembered it as, as a completely different book.

We'd all remembered Jean Brody as this rather eccentric, rather wonderful teacher that, you know, had all her girls in her thrall and now we went back to it and we realized that she's this sort of manipulative, fascist. It was, and I suppose, you know, we thought that's probably Muriel Spark's great skill is that she, you know, when we read it as teenagers, we saw her in the way that, you know, young students do see those sorts of maverick teachers.

So anyway, it made me admire it even, even more. And it was also interesting because it's set in Scotland and she has some, um, She captures that sort of atmosphere of Edinburgh and, you know, the sort of Calvinist, Presbyterian past. And I love what she says about Calvinism as being a terrible joke that we all used to believe in.

So anyway, so now I'm reading, and now I'm reading another Mandelbaum Gate, which is fascinating for other reasons because it's set in Jerusalem in just before the 1967 war. So that's a very interesting book to be reading in our present moment.

Zibby: Absolutely. Great. Well, Carys, thank you so much. It was a joy to discuss Clear with you.

Congratulations. And yeah, thank you for coming on.

Carys: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me.

Zibby: Okay. My pleasure. Best of luck. Bye bye.

Carys: Bye bye.

Carys Davies, CLEAR

Purchase your copy on Bookshop!

Share, rate, & review the podcast, and follow Zibby on Instagram @zibbyowens