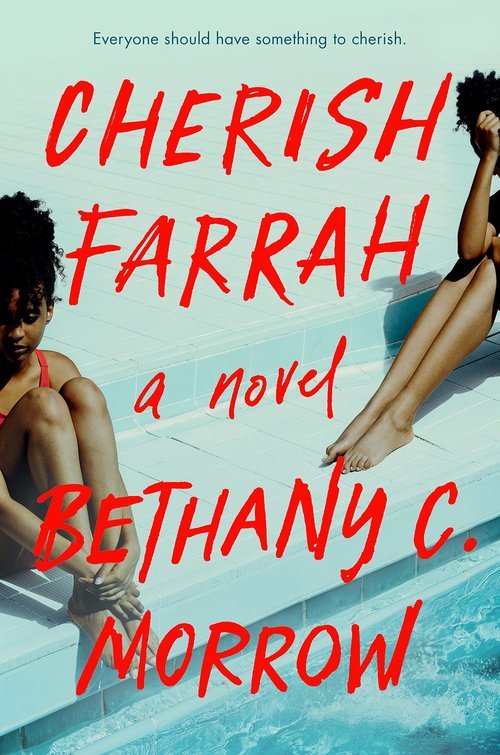

Bethany C. Morrow, CHERISH FARRAH

Bestselling author Bethany C. Morrow joins Zibby to talk about her latest novel, Cherish Farrah, which was Belletrist and BookClubs’ April pick. Bethany shares why she wanted to challenge white supremacist notions by creating a character like Farrah, as well as why she loves to write social horror. The two also discuss why Bethany jokes about being a contrarian, how she writes her books for group consumption, and Zibby reads Langston Hughes’ poem “Warning” which Bethany chose as the book’s dedication.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Bethany. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books” to discuss Cherish Farrah.

Bethany C. Morrow: Thank you so much for having me.

Zibby: I commented on this a minute ago. When I just casually picked up the book, you got this beaming smile when you saw it, which is so cute. I love that.

Bethany: I love my brain babies.

Zibby: Brain babies, that’s a nice way — a rebrand of books, little capsules of our brains. Would you like to see my brain? I don’t know. What is Cherish Farrah about? Please tell listeners.

Bethany: There are parts of Cherish Farrah that are difficult to talk about without giving spoilers. What I say Cherish Farrah is about is primarily a seventeen-year-old girl named Farrah who is very obviously not a typical teenager. She is one of two Black girls in a country club community, but she’s the only one with Black parents. Her best friend, Cherish, who she’s been friends with ever since, ostensibly, they came into this community and went to the academy, is named Cherish, and she has been adopted by white parents. She’s a transracial adoptee. Something that Farrah notices pretty immediately is that Cherish has this, what she calls, void, which is that she’s been coddled to the point of incompetence, according to Farrah, of course. She knows that because of that, she is able, uniquely, to fill that void. She’s pretty much the only person who could fill that void because of what Cherish is lacking and then because of what she’s lacking in terms of community. Her parents are these very progressive, very socially aware white parents who make it really clear that they’re being intentional about raising their Black daughter. They make sure she has a Black pediatrician and a Black orthodontist and that sort of thing, but what they’re missing is community. Farrah is really her only actual community. It’s basically about someone who believes that she is always in control but also possibly always thinks everyone is, like she is, trying to — I don’t want to say she’s paranoid because every time you think something strange, it doesn’t make you wrong. Because she is always playing chess, she believes that everyone who is capable is also doing the same. Of course, there’s a couple of people that she does not think are even capable of playing on her level. That is why the whole story happens.

Zibby: I love that you said that about paranoia because things really happen. I feel the same way about anxiety. Just because I worry — the things really do happen — that doesn’t make it anxiety. Forward-thinking, preparation, if you will. It’s the same thing. You had this expression about or this passage about how, basically, she’s like a spoiled white girl, but she’s not white, and how you can be a spoiled white girl inside even though on the exterior you are not. Of course, being spoiled in any race is not a good thing, but particularly not when you feel estranged from a community, as you said, which by the way, I feel like is the secret to really everything in any — if you have community, you can get through anything.

Bethany: There’s also communities that you cannot join and you can’t even be let into. A couple people can’t give you entry into it. Obviously, when you’re dealing with whiteness, we’re dealing particularly from an American perspective. We’re not dealing with a heritage. We’re not dealing with a culture. We’re dealing with a conglomeration of power. The thing Farrah knows that Cherish doesn’t know is why it’s a silly thing to say, because it’s not possible. Black is the same as white. It’s how you’re treated. It’s not what you are. It’s a social construct. Therefore, there is no way to be white-girl spoiled when you’re a Black girl unless your parents create this really nice little bubble. Then what happens if you ever burst it?

Zibby: That’s a great elevator pitch. That sounds amazing. Good job. Where did this come from? Where did this novel come from? Where did it come from?

Bethany: I know we all know that when we’re talking about books, because we know that books, even if they have a germ or a seed, a seed does not create a story. It doesn’t create a whole world of a novel. It doesn’t create fully fleshed-out characters, usually. Sometimes it does. When it’s really high-concept, it can. With Cherish Farrah, my agent actually said she would love to see something in a certain vein from me. As soon as she said it, I was like, no. I’m a contrarian. I’m not a short-order cook. I don’t like, oh, you would like a book about such-and-such? Let me do. Of course, I said no. She has to be super-duper patient all the time and just count down from when I say no about something. If my brain sparks — here’s the thing. I have a knee-jerk no reaction, but I’m also not married to — I’m willing to say, oh, no, I was absolutely wrong about that. Just kidding. I’m going to do it. I had a concept that has been fascinating me since I was a child, which is a book that actually is in this book. As soon as I knew that that was the vehicle, it was like, oh, no, I have to do this now. Of course, I’m going to do this. Because this is a social horror or a thriller, that’s sort of the twist. The rest of the story comes from Farrah herself.

For me, when you have social horror sometimes or the social horror that the majority of America is most familiar with, you tend to have almost a blank-slate character of a main character because you’re potentially trying to balance all of the stereotypes and anti-Blackness that our entire society is steeped in. I can understand saying, okay, I’m going to make a blank-slate character. There’s no way you could dislike this person. They have clearly done nothing wrong. It should make it really easy to see the commentary and to see the incisive dialogue and stuff that we’re having, but that’s not liberation to me. There’s no such thing as a perfect victim. Where white supremacy is concerned, it doesn’t matter who I am. It doesn’t matter what I do. I couldn’t be the problem. I could not be the problem when it comes to white supremacy. I was tired of that facile conversation where we have to start from a place, first, of going along with white supremacy and sort of defending the identity of Black people and defending the veracity of their concerns and their ability to be harmed by something that we know is systemic. I was like, what if the person that this is happening to is also a terror? Are you going to be confused? Are you going to be able to parse this story if she is herself a problem? Very early on, it should be pretty evident that she is a problem. What does that mean? Then who do you trust? Basically, what happens when they change their minds? which is my dedication. It’s an excerpt from Langston Hughes’ poem “Warning.”

Zibby: I can read it if you like.

Bethany: Yes.

Zibby: I do have it right here. “Beware the day they changed their minds”?

Bethany: Yes. If you haven’t read the context of that poem, I encourage you to go look up Langston Hughes’ “Warning.” It’s really good.

Zibby: I’m going to do it right now for everyone.

Bethany: She’s going to do the work for everyone.

Zibby: I’m going to do the work. It’s very short, so I can read it. Sorry, Langston Hughes. I hope this is okay. I’m kidding. “Warning. Negroes, sweet and docile, meek, humble, and kind, beware the day they change their mind. Wind in the cotton fields, gentle breeze, beware the hour it uproots trees.” Ooh, it’s good.

Bethany: Do you not love it?

Zibby: I love it.

Bethany: I had a different dedication. I remember sitting straight up and being like, phone, phone, phone. I had to email my team. Scratch that. Here’s the new one. I love the fact that I have to reply all to a group of people, and I got three emails directly to me, back to back, that were like, oh, my god, oh, my god, oh, my god. I was like, right?

Zibby: Really powerful. Amazing. Two things. One, I’ve never heard the expression social horror as a genre. Am I living under a rock? Is that the new term?

Bethany: I don’t think so. I think that it’s definitely a word or a phrase that has been in use. I don’t know how in use it has been outside of the Black community, the Black artistic community and the Black readership community, honestly. It’s specifically a type of horror that has to do with the world that we live in, the institutions in the world that we live in. The reason that I love social horror is because it’s demanding of the reader. It doesn’t allow for you to partake if you’re still going to hold onto your delusions. If you don’t know, if you pretend not to know what’s going on in this country — I won’t even speak to what has recently happened because we don’t have that kind of time and I don’t have that kind of bandwidth. If you try to pretend that you don’t know the identity of this nation and what it has done to Black Americans on top of everybody else — not at all to ignore what’s happening especially to Asian Americans right now, to indigenous Americans right now, to trans Americans right now. If you try to pretend that you don’t see those things, you are not the audience for social horror because it’s constantly forcing you to admit knowledge of something in order to understand a story.

Zibby: Noted. I like it. Excellent. I will start using that phrase. Thank you. I like it. I mean, I don’t like the fact that there has to be that phrase or that type of work. You know what I mean, I hope.

Bethany: Of course, that reality is such a terror that we can just write —

Zibby: It’s like truth is stranger than fiction kind of thing. Also, you briefly said you were a huge contrarian. What do you mean? Give me some examples, please. I want some juicy ones.

Bethany: This book was chosen was for Belletrist and BookClubs’ April selection. I remember saying it at some point in our conversation, which of course, they used in some of the footage. I’m being a little bit of a joke, of course, because I don’t think of myself as a contrarian. As this former student of sociology, I am not a direct result of my sociological training. Therefore, I’m not going to just go along with something or agree to something or even have a simple, on-the-surface conversation if something is said that clearly is problematic or something like that. Everyone wants to call themselves independent thinkers. Those words have ceased to mean anything at this point because it really usually just means, I’m seeking out evidence to confirm my preexisting bias. A contrarian in this sort of society, particularly a society like the United States which is founded on so much trauma and so much hostility and so much anger and so much evil, a contrarian could really mean anything in that context. For me, it means I am going to love at a capacity that doesn’t match the society that raised me. I’m going to identify, be able to love and have compassion and empathy for individual people despite — I’m not going to be forced into certain types of dynamics. I’m also not going to deny what I see. I’m not going to suddenly act like things like racist or something are debates and somebody can just say that they’re not something that they clearly are invested in. I personally, if you look at my family, if you look at my former spouse — I was running back to this because he called this morning. He was having car trouble, so I had to dash out and get him my car and then have him drop me back off here. It shouldn’t matter. I shouldn’t have to talk about it.

Since we’re going down a road where people are very clearly trying to undo things like the Loving case, like women’s rights, and that sort of thing and it very obviously has to do with these sort of white supremacist fantasies which always have to do with the subjugation of Blackness, it could eventually be a problem that my son is biracial, that my former husband is white American. A lot of people will try to tell you what you have to believe and how you have to feel about everyone if you identify as something. I say that I’m talking about an institution. I’m talking about an institution of power that has to be dismantled. Anybody who wants to dismantle it can. Anyone who wants to be involved in ending this can end it. I’m not going to apologize for that. I’m never going to apologize for my family. I’m never going to apologize for how I feel. They’re only my family, of course, because they come alongside and know all the things that I know and understand and appreciate reality for what it is and are supportive of all of my work and our family. Family is family. A contrarian in this country, honestly, could be anything. You could be somebody as benign as someone who loves someone they’re not supposed to. That’s a juicy example of something that’s been forcibly on my mind the past couple of weeks.

Zibby: I bet. Everyone needs to leave family out of everything, is my two cents. I’m just going to throw that out there.

Bethany: You would think.

Zibby: You would think. Tell me about writing this novel. Tell me when. Did it just fly out of you after you hit on this idea that this is the way you wanted to tell the story? How long? Give me the whole writing spiel.

Bethany: Oh, gosh, I can’t give you the whole writing thing because it’s totally different. I’m writing something right now that I’m fully, I want to say pantsing. My friend Dhonielle Clayton says — what is it? Headlights plotting. Literally just, I plot a scene, and then I write that scene. I can’t plot out a book because at that point, why didn’t I just write it? What are you doing? Why are we wasting time here? Which is funny because at a certain point with Cherish Farrah, I ended up writing an entire synopsis because we sold it as a partial. I did write out exactly what was going to happen for the whole second half of the book before I ever wrote it. Then I had to go away from it because I was actually writing So Many Beginnings, which came out the September before Cherish Farrah. I know that I had to have written it — the first chunk of Cherish Farrah was written in 2020 around the time that A Song Below Water was coming out, my young adult contemporary fantasy. Because of who Farrah is and because Farrah really is the story, and particularly, the story that carries you to the real story, the story that you know before you get to the story, it was really interesting writing her. I will say she was simultaneously the easiest person I’ve ever written and also the most difficult because I kept being like, what is she doing? Why are you doing this? Why are you doing this? She kept making things more complicated than they needed to be. She would work a situation out in three different directions. It’s like, they literally said, “Good morning.” Please, try to come down. Have some chill.

I, with my critique partner, Amy Suiter Clarke — I kept sending her chunks, as I do. I write, and I send her stuff. Some people say that writing is a solitary experience. It has literally never been for me. All of my first books were written for group consumption. I would write chapters. Then my sisters and one of my sister’s friends would read it. We would all sit around the computer. Then they would just read it out loud. At that time, I kind of was a short-order cook. I was sort of writing to specifically, okay, what do you want to see happen? It’s always been a social thing for me, writing. I wrote chunks. I would send it to her every day that I finished writing. It would always just be like, “I don’t know if I’m allowed to do this, but this is what’s happening.” It’s very difficult to be close to Farrah for any long period of time. She’s a strange person to be that claustrophobically close to. Of course, because it’s from her perspective and it’s her interior thought process, you cannot escape her. It was a very interesting writing experience.

Zibby: Tell me about being chosen for Belletrist and BookClub and all of that. What was that like for you? Who did you meet that was interesting as a result? That whole thing.

Bethany: I love Belletrist. They have really been supportive. I know they read Mem. I don’t think that we connected when they read Mem, which was my first novel. It’s another adult speculative literary, also science fiction, altered history type of deal. I know they had read that, but I think I found that out when I came on to do an interview for A Song Below Water, so sometime in either 2019 or 2020. I met Karah at that point. We just had the most absolutely amazing conversation. Then I kept seeing them posting about either A Song Below Water or Mem, which is really awesome. I love the way that they talk about literature. I love the conversation. It’s something that I feel like we’re at risk of losing if we don’t create these and don’t continue having these really intentional settings to do the work of really critical engagement with literature. It’s wonderful to just read books and love books. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. For me as an author, speaking to somebody who can speak about all of the different layers of the novel and can also extrapolate their own thoughts and can go off on tangents, that is why I do interviews and podcasts and that sort of thing. I love having those types of conversations. The types of reviews that I love have to have some critique. You don’t have to make something up. Seeing someone engage with the work that I labored over, for me, is always going to have a very different feeling than someone who just gushes. I love that. I love if someone enjoyed and can’t think of anything. I’ve done that before.

I will say, the times that I have gushed over something and could see no flaw with it, usually with time, I realize that I was totally hoodwinked. I’ll give you one example. I don’t know if everyone has seen Tron: Legacy. The music, the entire score was done by Daft Punk. Jeff Bridges is in it, of course. Just suffice it to say, I thought the movie was without error because of those two things. After a couple more watches, it was like, oh, okay. It was really Daft Punk, I think, that I was responding to. Maybe I’m projecting. Because I’ve had those kind of experiences where the inability to critically assess something usually meant that I was just having a completely emotional reaction, I have a lot of respect for the real work of literary critique. I think it’s so important. There are so many people who are doing just absolutely amazing — there’s nothing better than reading a really thorough — really, the scholarship of a criticism where they’re talking to you about the author, the author’s journey, they’re looking for the meaning that the author injected into their work, that’s really, really important. Having conversations with Belletrist always allows for that sort of discussion. I always really enjoy spending time with them.

Zibby: Amazing. Do you have any parting advice for aspiring authors?

Bethany: Oh, goodness. I usually don’t have a lot of the kind of advice I think that most people are looking for or giving because, especially with my own career, the most important thing is you have to know what you do and why you do it and what you want to do. I got so much advice that I completely disregarded from professionals, from industry professionals as well. Balance it with, do your due diligence. Research. Know the industry that you’re getting into is an industry. There are things that you need to know. Once you’ve done that, you need to know yourself and your work and your goals that well as well. This is where art intersects with business. You need to know what’s on the table and what’s not on the table, what’s negotiable and what’s not negotiable. If you don’t know that coming into this sort of industry, that’s going to be a problem. It’s going to be a problem for you because people are not really dedicated to mining that information and figuring it out for themselves. Everybody has something they’re trying to get accomplished. Know thyself.

Zibby: Love it. It’s great. Excellent. Bethany, thank you so much. Thank you for your passion and how articulate you are about the issues that you’re obviously thinking so critically about and that are so important to be thinking critically about and being able to communicate it and really rally the troops with your ardor and force. I love it.

Bethany: Thank you.

Zibby: And for that poem, which will give me the chills the rest of the day.

Bethany: Yes. It’s so good. It’s so, so good. Thank you so much for having me.

Zibby: Thanks for coming on. Take care. Bye.

Bethany: Bye.