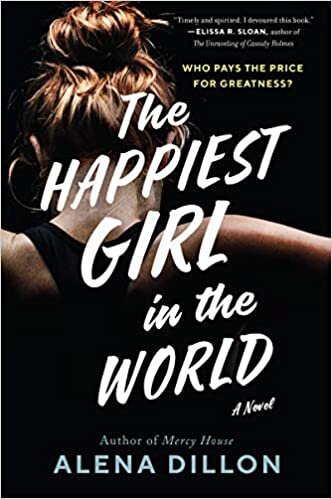

Alena Dillon, THE HAPPIEST GIRL IN THE WORLD

Alena Dillon joins Zibby to talk about the research on USA Gymnastics that went into her new book, The Happiest Girl in the World, as well as her upcoming memoir about pregnancy. The two share what they wished they had known going into motherhood and discuss the effects of parenting habits both on and off the page.

Transcript:

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Alena. Thank you so much for coming on “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.”

Alena Dillon: This is my absolute pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

Zibby: I’m so excited to discuss The Happiest Girl in the World, which is on such an important topic. I was just so excited to read it and talk to you about it.

Alena: Thank you. Thank you for having me. Thank you for everything that you’ve done for authors. I love this podcast. I love your entire brand. I’m just so happy to be here.

Zibby: Yay! Thank you. I like my brand too.

Alena: I know. All your newsletters, I’m like, what else is here?

Zibby: Thanks for subscribing.

Alena: Of course.

Zibby: Why don’t you tell listeners a little about The Happiest Girl in the World and what inspired you to write this book.

Alena: The Happiest Girl in the World is about a gymnast who is training for the Olympics and all of the costs of driving yourself that hard and pursuing something at that level and who it affects. Of course, it’s also about the culture of USA Gymnastics that we’ve all heard about. That’s part of the cost. It’s about a girl who sacrifices her childhood, the toll it takes on her body, the stress it puts on her family, on her parents’ marriage, on her twin brother, as well as her best friend. They’re kind of growing up in gymnastics together. Her best friend is abused by a doctor. Because of the culture of USA Gymnastics that we’ve all heard about and been horrified by, we know that there’s this silence and this pressure to be obedient and to defer to the coaches and to the officials and to stay quiet about things. The main character stays quiet and spends the rest of the novel punishing herself for it. That’s what the book is about.

It was inspired by the real events that we all know about. I started writing it in January 2018 during the Larry Nassar trials just because I was maybe ashamed, in a way, that I had not even considered the lives of the athletes in any of the sports. I just kind of tuned into the Olympics every two years and was entertained by them. Of course, there’s human beings behind those performances. If you’re going to be pushing yourself that hard, there’s going to be repercussions. I started asking myself a lot of questions about these organizations and how they’re built and what their priorities are and if they’re really keeping their athletes, who are children often, safe as well as a bunch of other questions about what happens to people who get injured and what happens to people who don’t make it and who have put everything into this dream and then miss it by a hair because so few do. I just did research and was exploring these questions.

Zibby: There was a lot, though, of actual gymnastics. As I was reading, I was like, you must be a gymnast or something, or you’ve been watching a lot of gymnastics.

Alena: I am not a gymnast. I can’t do any gymnastics except maybe a cartwheel. Yes, I spent a lot of time researching. I kind of got lost in a lot of gymnastics meets and the movements and was watching a lot of YouTube how-to videos just because I wanted to bring that physical sense because that’s what they spend so much time on. They spend years perfecting these minute-and-a-half routines. How many times do you do that over and over again? The reader should have that opportunity to live in those moments as well. Then because there’s just so much at stake in those movements, it’s a good opportunity to bring the emotional stakes into the air and have the physical and the emotional meet. I have to acknowledge that I hired an authenticity writer and a gymnast. Blythe Lawrence, she cowrote Aly Raisman’s memoir with her, I was really lucky to have her look it over to make sure that I was accurate because there was a lot of things that I just had no idea about that she was able to let me know. For instance, I thought a triple twist would be harder than a two and a half because the number’s bigger.

Zibby: Wow. I have to say, I felt like that was a big strength of the book because I felt literally like I was there rotating around the bars and my hands were holding — you definitely created such a sense of being there, which I feel like the best books do. I loved that feeling. Especially, I have a daughter who used to compete in gymnastics. I was in the locker rooms with the other moms trying to figure out how to do the hair the way you describe her mom doing. Obviously, her mom got a lot better than I did. I probably should’ve watched some YouTube videos about it, but I wasn’t that invested in my own success.

Alena: When the Larry Nassar trial broke and made headlines, I was actually finishing up Mercy House, my first book which has to do with sexual assault as well, and that time in the Vatican. I couldn’t help but see the parallels with the Catholic Church, USA Gymnastics, and then also Hollywood with the Me Too Movement. They were all this culture that is holding welfare hostage, basically, and often on women, but just in general in vulnerable populations. They have what these individuals want. They are forcing them to be obedient and quiet and to toe the line in order to give it to them. I was tuned into that already. Then the more that I researched about USA Gymnastics, the more I saw the specific ways in which they applied that kind of principle.

For instance, at the ranches, I found this memo that was posted by another parent of a gymnast that instructed the girls if they had any trouble in the middle of the night to call Larry Nassar rather than one of their personal coaches, so just funneling these girls to one particular person; when they were training, encouraging them to push through pain so that they just endured and tolerated. They were trained to endure and tolerate quietly. Then through documentaries and podcasts and then firsthand accounts, just how Larry was able to thrive because he allowed injured girls to return to the floor more quickly than some other doctors would. He was a useful expert to have on hand because he put the girls back into training. That’s one reason that he was able to stick around. When you’re approaching this world with that in mind, what are the ways in which these people kind of fostered an environment in which he could exist for so long? You find them. You find all their different strategies and the reasons behind it just so that they can push for success and have these girls have to live with things that are unlivable.

Zibby: I know. In the book when they called the doctor in, she was saying to her roommate, “No, go and get our coach.” She was like, “Oh, no, wait, we’re supposed to call the doctor.” I was like, don’t do it!

Alena: I know. Oh, my gosh, those were such difficult scenes to live inside.

Zibby: Ugh, oh, my gosh, and lifting up — oh, my god. It was a slow-motion thing, especially in a

Alena: It’s interesting to write something where you know that the reader will be built in with this knowledge already that the characters don’t know. It’s one of those moments where you have to keep that in mind. Then the tension is there from the start. It’s very cringy, but it’s powerful too because you can see how innocent the girls were. The reader always has the knowledge of retrospect.

Zibby: I also thought it was really interesting in the book how you profiled, essentially, a family and the effects on the family and all the costs associated and what you have to give up and all the things that this family had to forgo in order to channel everything into the one girl’s success. Then when something random happens like she gets poison ivy before a meet, what does that do to the family, and when parents aren’t necessarily on the same page? I love how you have part of it from the mom’s point of view too. This is where she’s coming from. What does it do to her and all of that? Tell me about that decision to structure the book that way.

Alena: That was totally my editor. That was a really fun suggestion. When I submitted the manuscript, it was all from Sera’s point of view. I had loved being inside the mom’s dialogue because she had a very distinct voice. When my editor read it, that was her big feedback. Is there a way that we can incorporate that point of view as well? With Mercy House, I had multiple-character point of view too. I had loved writing those chapters. As soon as my editor suggested that and I had already loved the mother’s voice, I was so excited to get going with that. I just went back to the manuscript and found some opportunities where it would be helpful to get the other side that maybe we don’t get from Sera and just to know the mother character even more. Those were really fun and also very painful.

Zibby: Also, it just makes you think about what it does to a child when the whole financial ecosystem of a family is relying on a child’s performance in a sport that should’ve just been fun. What does that do, just that pressure alone? Forget about all the horrific things that ended up happening to Sera and her friend and everything. Just that pressure, what does that do?

Alena: Right. The longer you’re in it, the higher stakes become because the more that they’ve sacrificed, quitting is — you can’t even consider it because you’ve been in it too long.

Zibby: I wonder what that ends up doing as you become a parent yourself and then you have to go through sort of the sins of the fathers lived on the youngers.

Alena: I know. The mother’s parents kind of dismissed her, so she wanted to move against that. She was acting against the way that she’d been raised. Then how will Sera move on? At the end of the book, I give a little insight into what she will be as a mother and having her own daughters and things. It would be interesting to know what choices she makes and doesn’t make based on how her mother treated her. You’re right. It’s also this kind of cycle.

Zibby: I once interviewed someone, John something Bishop, who said basically all of parenting is a reaction to everything that has been before you. Either you do what you liked or you go right against it. The real challenge is literally learning to parent in a vacuum as opposed to reacting one way or the other.

Alena: It’s stuff you don’t even think about. Just yesterday when I was — my son is two. I was doing our Easter ritual. I’m putting out the candy in the morning. My husband was like, “That’s what your parents did?” I hadn’t even thought about it, making this trail of chocolate throughout the house. Of course, that’s what my parents did. I thought that’s what everyone did. You’re just kind of baked in with stuff that resonates with you or stuff that you’re trying to balance out.

Zibby: That’s so sweet. We always did a birthday breakfast. Finally my husband is like, “Why are we always having cake for breakfast?” I’m like, “Doesn’t everyone have cake for breakfast?” He’s like, “No, I have cake for dinner.” I don’t know why we had that tradition. Yes, it makes you question. Tell me more about how you got into writing to begin with, Mercy House, this book, your whole writing trajectory. Did you always know you wanted to be a writer?

Alena: Yes, I did. From when I was very little, I was reading adult books. I went back and found my fourth-grade yearbook. I had written, favorite book was Separate Beds, which was this thick romance novel that I had found of my mom’s. I started writing my first book when I was ten. I just always wanted to be a writer. I have always pursued it, much more seriously after college. It’s been a relentless pursuit since that time. It took about ten years from after college to getting Mercy House published. There were a bunch of books in between and a couple different agents and a lot of submissions, a lot of close calls, a lot of rejections. I guess it was 2018 that I signed on with my agent. Then it rolled so quickly after eight years of nothing. It was just all of a sudden, we had interest from Hollywood. We were fielding phone calls from different producers and things. I couldn’t believe it because sometimes it feels like it’s just never going to happen. It’s embarrassing. People are like, how’s the writing going? You’re like, it’s still going. I’m still writing. Then all of a sudden, I’m on the phone with Amy Schumer. I’m going to meet her in New York. It feels absurd and magical. Since then, I have this book now coming. I have another one coming in October and another one slated for next year. Once you find the right people, then opportunity just begets opportunity. I’m just so lucky. It’s conceivable that it could take however long. If I hadn’t submitted to my agent then, who would have been maybe the next person? How long could it have taken? Would I just have given up at some point? Maybe. Maybe not. It seems like it takes some talent, a lot of hard work, but also just tons of luck to find the right people at the right time.

Zibby: I’m sure you’ve also gotten so much better. Not that you weren’t an amazing writer to begin with, but just think about ten years of practice versus someone sending out their first draft of something. You had all that time to get better. I wish there were a way in the writing universe where you could not feel like a total reject while you learn because the only way to learn is to try and fail. That’s part of the process, but it doesn’t feel like it’s part of the process. It feels like a complete failure and like you’re never going to get there.

Alena: Malcolm Gladwell actually calls ten years the magic number. That’s usually how much it takes to get those, is it forty thousand hours of practice before you become really good at something? It’s so true. I definitely can’t look at manuscripts that I wrote ten years ago. Even if I’m flipping through Mercy House, I’ll find sentences that I’m like, oh, I would’ve cleaned that up. You’re constantly evolving and coming up with a different style. Hopefully, we just keep getting better and better.

Zibby: Wait, so with all your Hollywood discussions, where did that end up?

Alena: Mercy House, it’s in development as a television series. As far as I know, they have written the first episode and are looking around for casting.

Zibby: So exciting. That’s so cool. What are the next two books about?

Alena: I have a memoir coming out in October called My Body is a Big Fat Temple. It’s about my experience with pregnancy and early motherhood. Whenever I go through any experience, I look for books about it so that I can kind of know what to expect and then also feel less alone if I’m going through something knowing that somebody else went through it. There just wasn’t a lot of material. There were some books, but a lot of them were how-to books or nonfiction about the science of pregnancy. There wasn’t a lot of just narrative of the journey of going through it. I felt like I kind of was caught off guard by a lot of the experiences and how primal it is and sometimes a little gruesome, and if you’re feeling anxiety. A lot of the experiences are just romanticized because we like to keep motherhood as this ideal. I wanted to approach it with a bit more honesty and grit and humor. That’s coming out in October. Then I have another novel slated for next year about a woman Air Force service pilot during World War II and her daughter sixty years later and how being dismissed as a pilot after the war was over kind of affects the inheritance of the girl. She’s living with her mother’s regret, so I guess more of that cycle of parenting, the experience of the mother and how that affects the motivations of the daughter.

Zibby: Wow. Those all sound great. I’m dying to read your memoir. That sounds so good, oh, my gosh.

Alena: Thanks. I’ll send you a copy.

Zibby: Please do. Nothing really can prepare you for pregnancy when your body is taken over and all your old issues come up.

Alena: No one really talks about how difficult — maybe people are starting to more. I didn’t feel like people had talked about the loosening of your joints and the carpal tunnel and how your body just kind of implodes on itself. The cost of creating life is astronomical in a way. There’s this hush. Don’t tell them or they won’t want to do it.

Zibby: You’re supposed to forget it. Your mind forgets it. I started with a twin pregnancy. That was horrific. I was on bed rest, honestly, most of the time. I am not a good candidate for bed rest. I can’t sit down most of the time. Parts of my body, they’ve never been the same since.

Alena: Yes. They don’t talk about either, how you live with these effects forever.

Zibby: I ended up having four kids. My younger daughter the other day was pointing to my stomach. She’s like, “And that’s because of,” and she said my older kids’ names. I was like, “Yep, and that’s okay because I’m so blessed that I have them.” Yes, I have this disgusting stomach because of it, but I’ll take it.

Alena: I know. People talk about, how many stretch marks do you have? I’m like, I look like I laid face down on a towel sunbathing. My belly is terrycloth. I can’t count them.

Zibby: My OB, actually, when I was pregnant, I was saying something — at the time, I was so concerned about my body. Not that I’m not, but I was just racked with — I had spent all this time trying to lose weight. Then I got pregnant. Of course, forget it. I remember my OB who had also had twins was like, “I just want to warn you, you’re not going to necessarily look the way you did before.” She literally lifted up her shirt and showed me her stomach. I was like, “Oh, don’t show me that.” I can imagine being in that room so well like it was yesterday. Of course, I don’t look so different. I felt like that was my warning, one woman to another, one mother to another in the privacy of an intimate doctor’s office just showing me what’s to come. Otherwise, how do you get this information?

Alena: That’s right. That’s kind of what we’re trained to do, is that cloak and dagger, lift up the coat and reveal what’s the truth. I don’t know why the discourse isn’t just more straightforward. I’m just a much more direct person. If somebody asks me what it’s like, I’m going to tell them. That’s what the book is about because I was looking for — the experience is so different for everybody, so you need to collect all of these experiences even just to piece together something that will be what you recognize. I think we need to have more stories so that people know that they’re not alone. If they are feeling something and that’s not something they’ve heard of, you really feel isolated and like you’re an anomaly. That’s a scary feeling.

Zibby: That’s so true. Although, do I want to go back there? I don’t know.

Alena: Exactly. That’s true.

Zibby: Then of course, you have this trail of memory following you around like a tail behind you. Should I turn around and look, or should I just let it whack the ground?

Alena: Like you said, your body’s now a map of it too.

Zibby: Yes, exactly. That’s so exciting. When do you write? What’s your process like?

Alena: I write in the mornings. I’m really lucky to have — my husband has a flexible work schedule. He’s a professor, so he arranges all of his classes to be afternoon, and especially with the pandemic. We don’t have childcare. I wake up, and I have the morning shift every day. Then he has the afternoon shift. Then we both work after my son goes to bed. We both work weekends. I write every day in the morning. That’s my spot.

Zibby: Right here where we’re doing our little Zoom?

Alena: I write in my bedroom. This is the basement where I’m holed away. It’s more quiet. I write usually in my bedroom. It has a little writing desk. We just had to change the knob because I didn’t have a lock on it. My son has learned now to turn the knob. Now there’s a locked door. Occasionally, there’s knocking on the door calling for me. I have a YouTube rain video that I put really loud. I write through thunderstorms every day.

Zibby: Wow, interesting. I’ll think of you next time it rains and be like, you can turn off your YouTube today.

Alena: You need a lot of sensory ques to work. I like having my coffee and that smell. The motion of bringing it to my lips puts me in the mood. Now the rain puts me in the writing mindset.

Zibby: There is something so great about a rainy day. It’s so interesting that you recreated that cozy intimacy of it. Then you can just close the laptop, and it’s gone. How great.

Alena: That’s right. Yeah, go outside.

Zibby: What advice would you have for aspiring authors?

Alena: Let’s see. A huge one for me is to have reading partners. After I finish a manuscript, I find it really hard to get perspective on what needs to be changed. I have a sense that maybe it’s not as strong as it can be, but I can’t see it for myself. I need a few opinions to point out things to me. Then I see if that resonates. My husband’s actually a really good editor. He reads it over a couple days. He’s really good at marking it up. Then he tells me. Then we don’t speak for a couple days.

Zibby: Do you finish the sentence, or do you stop mid-sentence?

Alena:

Zibby: That is awesome. Yeah, the blank page is so intimidating. Sometimes when I’m trying to write something, I just put it in an email because I’m like, email is so non-threatening. I’m just going to start it as an email.

Alena: Oh, that’s a good idea.

Zibby:

Alena: Right, the blinking cursor.

Zibby: I’m just like, I can’t deal with that. I’m just going to pretend this is an email to a friend. I’ll start it that way.

Alena: Good idea.

Zibby: Anyway, amazing. This is so great. I can’t wait to read your memoir. I’m so glad I got to read at least most of The Happiest Girl in the World. Now I want to watch Mercy House when it comes out. So much exciting stuff. I’m just so glad our paths have crossed. Congratulations on all your stuff. I’m glad you found your agent.

Alena: Me too. That’s a blessing.

Zibby: Awesome. Thank you so much for coming on. Best of luck.

Alena: Thank you for having me. Bye. Take care.

Zibby: Buh-bye.